Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Case Study of an International Asian Filmmaker

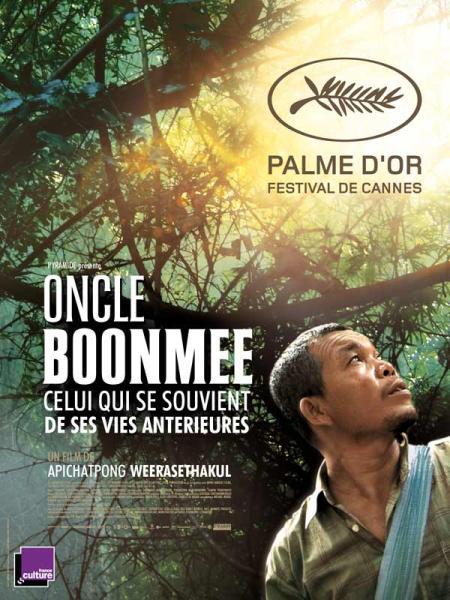

In May 2010 Apichatpong Weerasethakul won the Palme d’or at Cannes for his feature Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall Past Lives, and thus became the first Thai director to receive the crowning award of the world’s most prestigious film festival. This marks the apogee of Apichatpong’s steady progression in international praise and visibility (if not exactly household fame), with his previous films having been awarded lesser Cannes trophies and his work extravagantly praised by the most prominent critics in France, Britain and the USA. Western enthusiasm for Apichatpong has translated into financial as well as critical and ceremonial terms: a glance through the credits of his films reveals a roster of European and American production companies and funding bodies, including German state television and the French Ministry of Culture and Communication.

In May 2010 Apichatpong Weerasethakul won the Palme d’or at Cannes for his feature Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall Past Lives, and thus became the first Thai director to receive the crowning award of the world’s most prestigious film festival. This marks the apogee of Apichatpong’s steady progression in international praise and visibility (if not exactly household fame), with his previous films having been awarded lesser Cannes trophies and his work extravagantly praised by the most prominent critics in France, Britain and the USA. Western enthusiasm for Apichatpong has translated into financial as well as critical and ceremonial terms: a glance through the credits of his films reveals a roster of European and American production companies and funding bodies, including German state television and the French Ministry of Culture and Communication.

The novelty of a Thai filmmaker being elevated among the major international auteurs belies Apichatpong’s typicality, the extent to which his career epitomises the globalised, transnational character of contemporary cinema. The film world is increasingly one of porous national and regional boundaries, and with their dependence on international backers and rapturous reception by Western critics, Apichatpong’s films could be considered a ‘highbrow’ parallel to the intense current engagement between US and East Asian cinema that has resulted in co-productions and, more dubiously, Hollywood remakes of Asian action and horror films. Moreover, Apichatpong’s career is closely bound to the transnational space of the film festival, now seen as both the dominant institution through which art film directors’ reputations are established and foreign distribution secured, and an ‘alternative exhibition circuit’ where the most ostentatiously uncommercial films have a good chance of being screened (de Valck 2007: 106). Like the much-garlanded Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami before him, Apichatpong has arguably benefited from the cachet of ‘exotic’, non-western cinemas at festivals, which compete in their attempt at new and ever more rarefied discoveries. Yet the contemporary film festival has been said to stress the idea of ‘autonomous auteurs’ over that of national cinemas, and thus to help foster a ‘post-national’ film culture (Elsaesser 2005: 83).

Not only does Apichatpong exemplify our contemporary ‘transnational condition’ through the production and reception of his films: he also inscribes it in their content, and for this he has been considered a poet of the transnational. His Thailand often comprises a space of blithe cultural hybridity in which mass-produced Western lotions and traditional remedies, Pepsi and papaya, can comfortably coexist. In itself the amused depiction of such incongruities is easily situated in a ‘Western’ postmodernist mode, and one might surmise that Apichatpong’s enthusiastic reception abroad has been aided by his apparent refashioning of familiar tropes and techniques, the appealing synthesis of Western formalism with an Asian face. Indeed Apichatpong has acknowledged the impact of the American avant-garde filmmakers whom he discovered as a Masters student in film at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The influence of Andy Warhol, for instance, is considered evident in Apichatpong’s concern to portray real time, in those long, static takes that frequently chart only the most infinitesimal developments, and yet an aesthetic of stringent duration equally connects Apichatpong with exponents of the so-called ‘Contemporary Contemplative Cinema’ school that traverses both Europe and Asia (Ingawanij and MacDonald 2009: 122). Beyond cinematic influences, Apichatpong’s solo feature debut Mysterious Object at Noon (1999) is to my knowledge the first film whose narrative is constructed around the principles of the French Surrealists’ ‘Exquisite Corpse’ game, in which a text or illustration is concocted by multiple participants in turn. I also find a subtler Surrealist tenor in the bravura, mid-way transformation of the halting gay courtship of Tropical Malady (2004) into a supernatural tale of pursuit, mystery and literally animal desires. It is hardly inexplicable that British producer Keith Griffiths, a long-standing supporter of Surrealist animators Jan Švankmajer and the Brothers Quay, should have co-produced Apichatpong’s last two features.

Domestically, the ‘Western’ or ‘international’ character of Apichatpong’s cinema has been defined in negative terms, with the charge that his films are of little interest to local audiences and even somehow ‘un-Thai’. The notorious decision to censor several scenes from 2007’s Syndromes and a Century by Thailand’s recently installed military government might well underline that his work is unwelcome at home, while the head of the department that requested the cuts flatly declared that in Thailand, ‘Nobody goes to see films by Apichatpong’ (Montlake 2007).

Such commentary on prejudice and racism in Apichatpong’s work reminds us that barriers and boundaries persist in our world of supposedly unchecked intercultural hybridity. This is one way in which Apichatpong’s work proves more nuanced and ambivalent than the image of the insouciant chronicler of transnationalism and cultural fluidity would suggest. In Blissfully Yours, the character of illegal Burmese migrant Min points to how transnational movement is for many a necessity impelled by the desperate economic conditions of their homeland, while the sight of Min’s factory worker lover Roong painting Bugs Bunny figurines on a production line conjures up the darker side of globalisation in the form of outsourced labour and neo-imperial economic relations. That Blissfully Yours depicts an idyllic moment of relaxation and erotic pleasure for Min and Roong in the Thai jungle – a respite from both work and the anxious quest for it – complements Apichatpong’s customary visual accent on stasis, stillness and slowness: such qualities might be seen as a subtle corrective to the restless mobility, ceaseless flux and communication overload of our globalised, mediatised world. Apichatpong is a filmmaker of contradictions and dualities, attesting simultaneously to the liberating and repressive character of modern life and skirting the wildest shores of the Western avant-gardes while remaining richly, sensuously immersed in specific Thai realities.

by Jonathan L. Owen

References:

Bradshaw, Peter. ‘Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives – review’, The Guardian, Thurs, Nov. 18, 2010 (http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2010/nov/18/uncle-boonmee-who-can-recall-his-past-lives-review)

de Valck, Marijke. Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007)

Elsaesser, Thomas. European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2003)

Ingawanij, May Adadol and Richard Lowell MacDonald. ‘Blissfully Whose? Jungle Pleasures, Ultra-modernist Cinema and the Cosmopolitan Thai Auteur’. In The Ambiguous Allure of the West: Traces of the Colonial in Thailand, ed. Rachel V. Harrison, Peter A. Jackson (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2009)

Montlake, Simon. ‘Making the Cut’, Time, Thurs, Oct. 11, 2007 (http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1670261,00.html)

Jonathan L. Owen is a researcher and writer whose primary interests are European and Asian cinema and their relation with the avant-garde. He completed his Ph.D. at the University of Manchester in the UK, and since then he has published journal articles and a book about the Czechoslovak New Wave.

Similar content

09 Mar 2011

posted on

25 Dec 2014

posted on

12 Feb 2019

posted on

06 Nov 2018

posted on

08 May 2011

posted on

09 Sep 2016