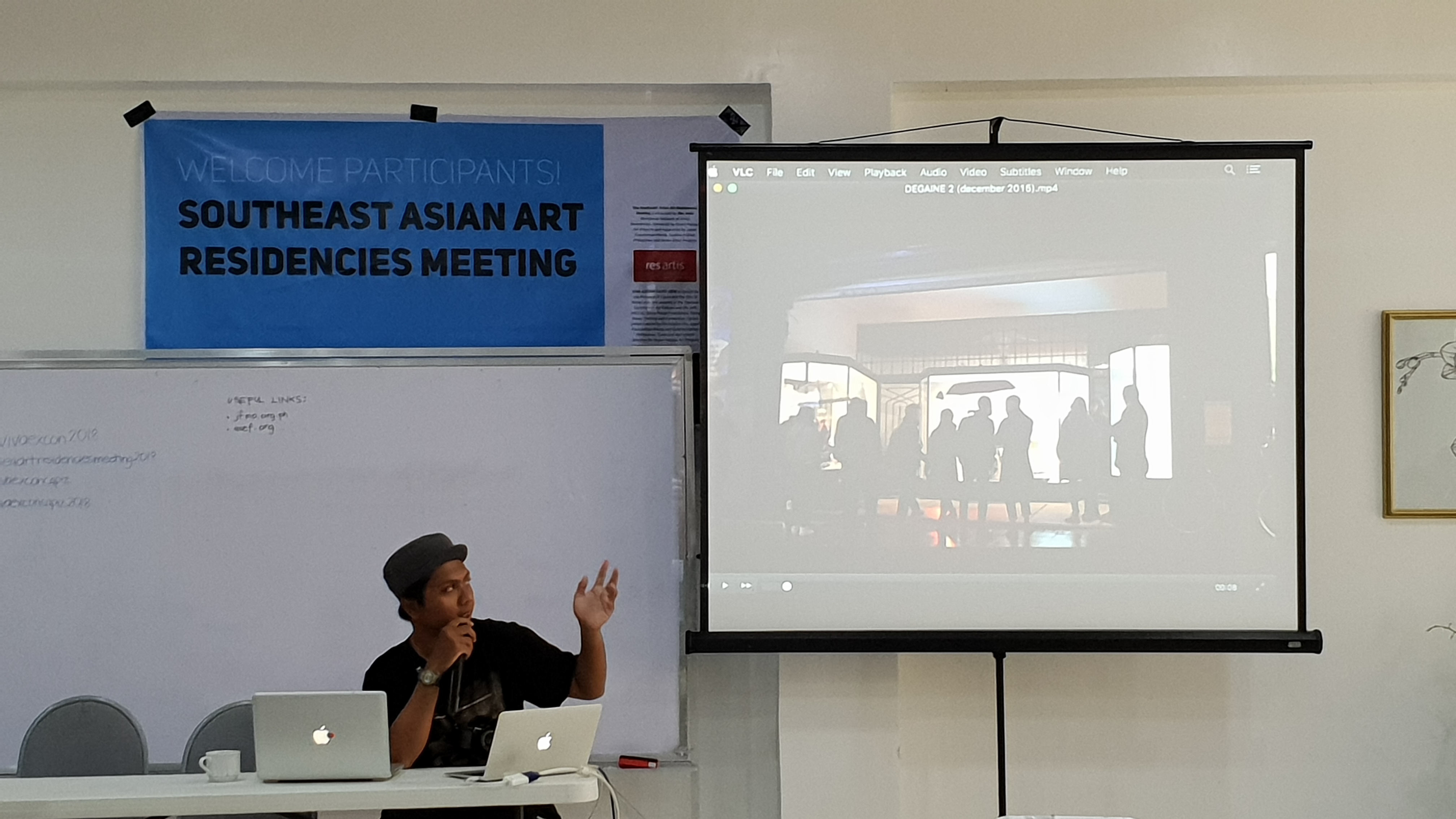

Key Insights from the Southeast Asian Art Residencies Meeting 2018

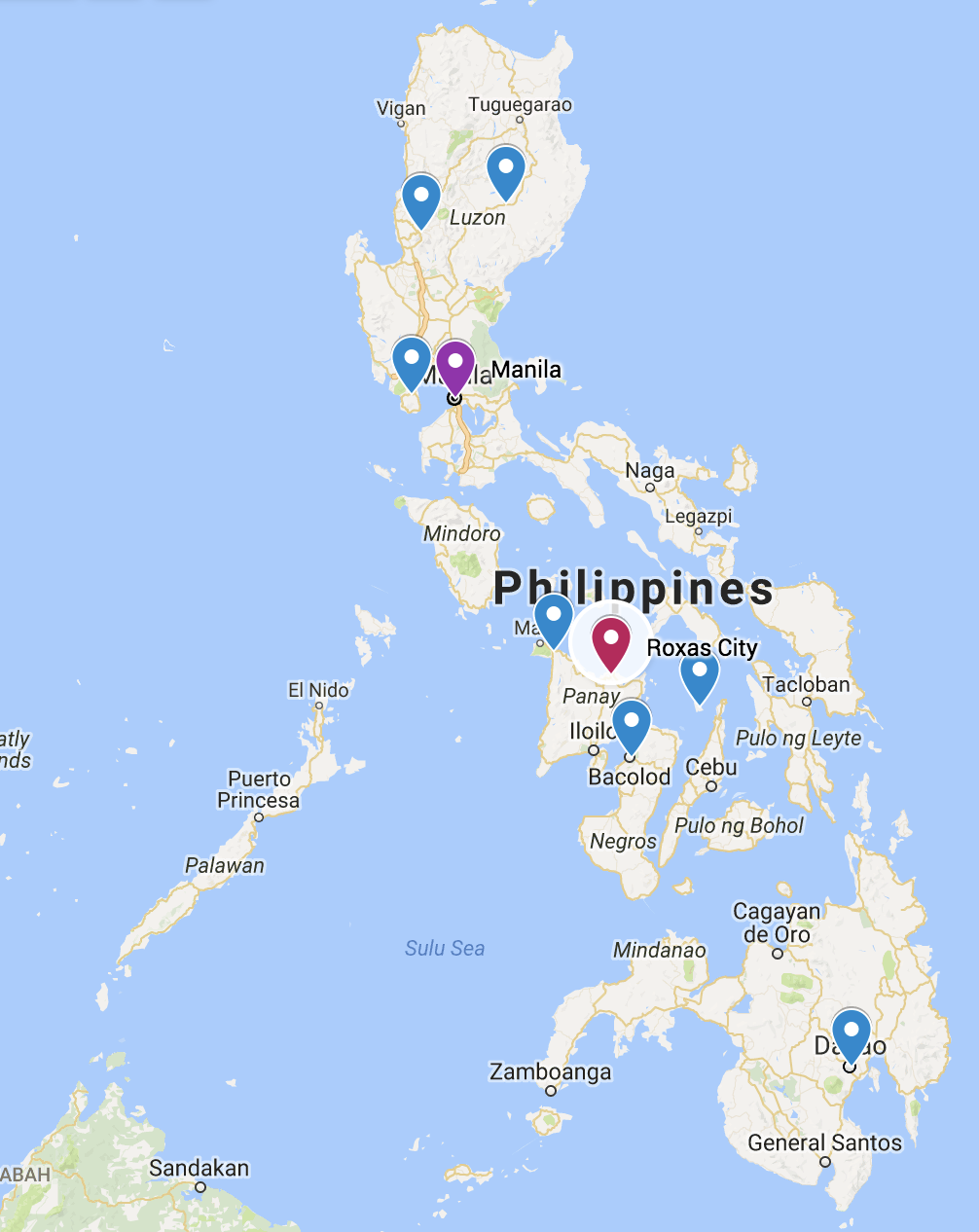

On 20-22 April 2018, over 50 representatives of 36 residencies and arts organisations from 9 Southeast and East Asian countries gathered in Roxas City in the Capiz province of the Philippines, situated 440 kilometres from the capital, Manila. The Southeast Asian Art Residencies Meeting 2018 was organised by Green Papaya Art Projects (Philippines), an independent artist-run initiative led by Norberto “Peewee” Roldan, Artistic Director, and Merv Espina, Programme Director.

Green Papaya convened the 2018 meeting, with the help of 98B COLLABoratory, after both were inspired by the success of the 1st regional meeting of art residencies in Southeast Asia that took place on 20-23 July 2016 at Rimbun Dahan (Malaysia), an arts centre outside Kuala Lumpur that runs one of the oldest art residencies in the region.

Similar to the aim of the Malaysia meeting, the 2018 edition held in the Philippines is meant for participants to share their contexts, challenges and strategies in starting and sustaining residency programs without looking through a Western lens, thus focusing on problems closer to home, and with an added emphasis this year of strengthening arts communities outside Metro Manila and other capital cities in the region.

The meeting is one of the major lead up events to VIVA EXCON - Visayas Islands Visual Arts Exhibition and Conference - the longest running artist-run biennial in the Philippines, which will also be hosted by Roxas City in November of this year.

The participants trickled into Roxas City on 19 April by various modes of transport: representatives from international arts organisations and those coming from Manila came by plane while those travelling from neighbouring cities and islands arrived by bus or boat or a combination of all forms of transport. The Philippines is an archipelagic nation comprised of 7,000 islands and travelling outside the capital is not a simple affair.

While the lack of funding for cultural mobility remains the biggest barrier for in-person dialogue, the challenging nature of transport in the country makes meeting for local organisations from across islands an equally rare opportunity as a gathering among international organisations in the region. The Southeast Asian Art Residencies Meeting 2018 gave reason for both rarities to occur.

Current State of Affairs and Opportunities

The forum began with laying down the premise and current topography of art residencies in Southeast & East Asia.

Art residencies play a huge role in the learning process of artists, they are catalysts for communities in terms of local development, and in some cases like Japan, they are a recognised part of a cultural portfolio that leads up to a big national event like the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. No one doubts the useful and creative purpose of art residencies. The question is more on dealing with the challenges that come with running a residency.

An art residency seems to be a straightforward experience: an artist spends time temporarily residing in an art space elsewhere, creates new artworks, then exhibits the artworks. In the process of creating new artworks, the artist may engage the immediate community of the residency venue.

But not all residencies are success stories. In fact, many participants shared stories of “failure” and 2 recurring themes in the stories were: 1) mismanaged expectations, and 2) end goals not reached. Mismanaged expectations occur when demands from resident artists cannot be fulfilled by the residency. There are many reasons for this: sometimes the demands onsite are unreasonable, other times it is a simple case of the artist not reading the guidelines of the residency or the residency not communicating the practical situation of the venue, and therefore expectations on the artist’s end were outside of what the residency was able to provide (e.g. an artist expecting the residency staff to take him around the city, or providing him with all meals during the residency, or expecting the residency venue to be a vibrant place when the reality is isolation).

On the other hand, reasons for end goals not being reached may include not being able to finish the artworks agreed upon and therefore not being able to produce an exhibition, which was the expected output. But a question was raised for residencies that have no tangible outputs i.e. research residencies – since no concrete outputs are expected in this case, how does one prove that the artistic process was present?

Sometimes, conflicts arise because of the absence of formal agreements. While the art world operates mainly on personal relationships, written contracts prove to be useful especially when one party reneges on obligations. But when there are no formal agreements or contracts, it becomes a messy situation.

A section of the forum was dedicated to how residencies can navigate cultural agencies that provide funding for them and the opportunities that currently exist. The Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF) and Japan Foundation - Manila were the guest speakers for this part and representatives of both organisations presented their programs that were relevant for art residencies.

Goals for Emerging Residencies

The meeting looked at the different stages of a residency space and program. In the stage of starting a residency, 2 main topics were tackled: 1) knowing the purpose for doing it, and 2) creating a strong core team.

There are different reasons for starting a residency, including something as straightforward as making new friends, or expanding one’s professional network by creating a platform for cultural exchange. Other participants said it was a natural next step for an existing exhibition space that wishes to expand. Another reason was to create a new means for additional income. For others, there is a social dimension - a residency could invigorate the immediate community. In one unique case, the reason was for legacy: a widow was transforming their house into a residency space after her husband, who was a prolific artist, passed away.

But whatever the reason may be, it is integral that the purpose should be very clear. Once the purpose is clear to the core team that will initiate the residency space and program, everything else is just a matter of implementing details.

How does one create a strong team and sustain the commitment of the core group executing the residency? One strong suggestion was that a residency should be founded by a collective. The reasoning is not so much about democracy or the organic nature of a collective or its flat structure, but rather, it is because it is easier to initiate something together, and therefore, to address crises with a united front.

However, several participants in the meeting were employees who are not necessarily founders or part of a collective that owns and runs a space. Yet, employees are also part of the core team. In the field of arts & culture, team sizes are usually very small, and every member of the team is core.

Further, people who choose to work in the arts have a great deal of passion: those who believe in the cause will stay to do what is necessary to deliver a project, and those who don’t, will not. However, the importance of salary was brought up and how this is also an important factor for staff. At the end of the day, self-care is vital. People need to be able to sustain themselves first in order to be effective in doing what they are passionate about.

Engaging with Communities

Several residencies shared how they engaged with their immediate public, which were a variety of groups including townsfolk, the local government, indigenous peoples. One representative shared difficulties sustaining his practice in his island because the people in his town only perceive someone as successful if he/she leaves the island. Moreover, he is ill at ease practicing as a photographer because when he takes photos, the townsfolk comment that he is pretending to be a tourist and doesn’t have a real job. Another participant shared that a large part of his work is chatting with people in his immediate proximity, which includes his local government because the office is very near his space. Another participant shared that her immediate public is a group of indigenous people, and she shared the ethical concerns that come with community-based art, e.g. are we doing more harm than good?

Also, the aim of community-based art is to evolve into participatory art that results in social change.

The concept of increased cultural capital was brought up during the discussion of community-based art. One can argue that a resident artist benefits from increased cultural capital after a residency and that may open new doors for him/her. But how did his visit benefit the community conversely? How is this measured?

There was also the predicament of community vs audience: what is the difference and are there different modes of engagement for either? In the end, a general opinion was stated that arts practitioners have the power to be catalysts for change in redefining measures of success, of what a real job is, of engagement, of benefit, depending on one’s context.

Other organisations are also part of one’s community. For residencies, reciprocal relationships with organisations that organise festivals or other residencies are always beneficial and these relationships can also influence programming. After all, the context is the program.

Evaluation and Sustainability

Having archives is extremely important for an art residency. Archives keep history intact and provide good reference for the residency itself, alumni, and prospective artist residents. However, many older residencies in the region are struggling to maintain archives because of changing technology (i.e. older archives are in floppy disks, CDs, and printed hard copies), and the existing challenges of funding and dedicated human resources. All participants agreed that maintaining up-to-date and accessible archives is a must.

Participants also recognised the importance of monitoring and evaluation. A residency program should be monitored on a regular basis and evaluated by an independent evaluator who is not connected to either the residency itself or a funding body that supported them. What kind of feedback should be pre-determined e.g. is it only about technical and practical details like facilities or will it include curatorial direction and programming? Clear guidelines and a set of criteria should be provided to the evaluator.

It is extremely difficult to quantify or qualify the artistic process and its results. In terms of evaluation methods, many agree that methods outside the realm of indicators and scorecards should be explored. A “creative evaluation” is more apt for residencies and more analytical depth is provided by qualitative data such as storytelling.

Therefore, questionnaires and interviews are encouraged but they should be objective and data-driven. There are softwares now like Deduce and Envivo that are able to analyse data and present them in an objectively presentable manner. For the interview method, it was suggested that artists be interviewed before, during, immediately after…and after some time has passed (it could be years), in order to get proper feedback, especially since perhaps the artist would have gone to another residency and would have points for comparison.

Changing the model of an organisation is one topic brought up for survival. Residencies who have been operating for more than 15 years are re-thinking their operational models. In line with the need for monitoring and evaluation, a constant re-thinking should also be present: Is what we are doing still relevant? Is it sustainable? How can we make it better? Should we change it slightly? Should we change it drastically? The direction for change for older residencies seems to be shifting from a traditional residency model to a full blown education program. While nearly all participants recognise the need for a strong education arm, and in fact, many existing residencies have an education aspect in their programming, one organisation is fully converting itself into an art school. Other participants concurred that this is a good move, and pointed out that after all, one purpose of artmaking is knowledge production.

The Southeast Asian Art Residencies Meeting was indeed an unprecedented gathering of both local and international arts organisations in the region. The sharing of current practices, shared challenges, available opportunities, and future directions were inspiring for all those present. Hopefully, this meeting will be an impetus to strengthen regional connections and intra-Asia networks that will forge fruitful collaborations in the future.

The Southeast Asian Art Residencies Meeting 2018 was organised by Green Papaya Art Projects with the help of 98B COLLABoratory. The project is endorsed by Res Artis (Netherlands), the largest membership-based global network of art residencies, and received support from Goethe Institute - Philippines, Japan Foundation - Manila, Gerry Roxas Foundation, Bellas Artes Projects, and the Provincial Government of Capiz.

Green Papaya Art Projects is also setting the artistic direction for the VIVA EXCON Art Festival in the Philippines in November, for which the Southeast Asian Art Residencies Meeting 2018 was a major lead up event for. The team is comprised of:

Peewee Roldan, Artistic Director, Green Papaya Art Projects

Merv Espina, Programme Director, Green Papaya Art Projects

Neo Maestro, Residency Manager, Green Papaya Art Projects

Marika Constantino, Executive Director, 98B COLLABoratory and Co-curator, VIVA EXCON

Iris Ferrer, Managing Curator, VIVA EXCON

A better formatted and print friendly version of this article can be downloaded here: Article-SEAResidenciesMtg-ASEF-260418.pdf

The organisers will upload the programme and directory of residencies present here: http://cargocollective.com/vxcapiz2018/Southeast-Asian-Art-Residencies-Meeting-2018