Museum of Material Memory: Unlocking of the Lived Past through Ordinary Objects

As part of culture360 recent Call for articles, Roli Mahajan explores an online museum that uses much-loved objects to initiate a journey into generational narratives about tradition, culture, customs, habits, language, society, geography and history of the Indian subcontinent.

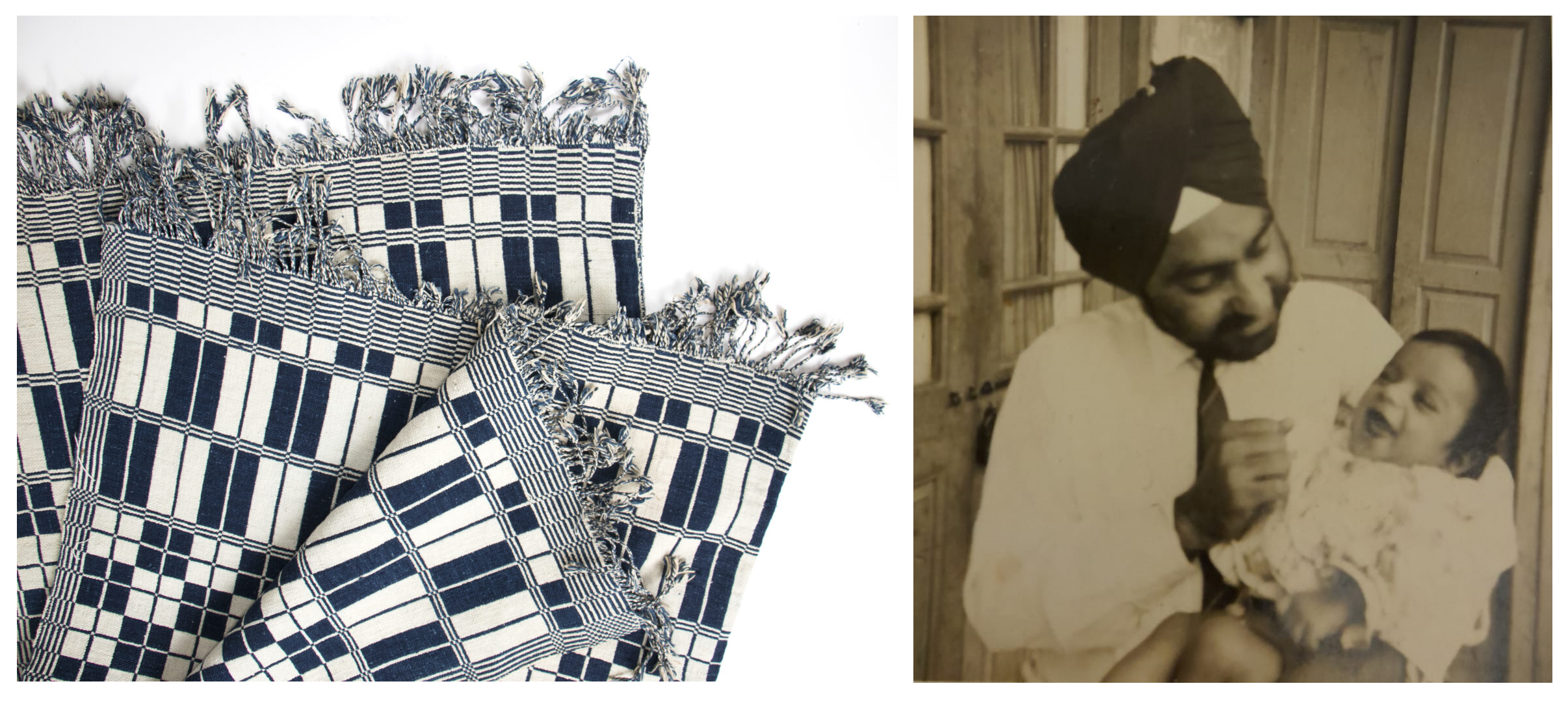

Once, two students of textile design were documenting old traditions of handicraft when they chose to focus on a particular kind of hand-woven material from the Indian subcontinent that was used for making blankets. Fieldwork in the Indian state of Punjab yielded no results. Despite consistent research efforts and meetings with several weavers of repute, the students were unable to find any trace of this “double-weave fabric, a compound weave structure” called Majnu Khes. That was until one of the students, Arjunvir Singh, spoke to his mother and was told that his grandfather used to own one such Khes, which he never let anybody use. His grandfather had bought this when he was young and the sub-continent had still not faced the mayhem of partition. Further investigation revealed that the reason why no one on the Indian side of the border could answer Arjunvir’s questions was that this particular type of weaving was done by Muslim weavers, who were now in Pakistan.

This account that touches upon the personal, social and political life of a mundane object, is one of the many that make the Museum of Material Memory.

1. Majnu Khes, Punjab, Pakistan, (West Punjab, before partition of India), article from before the partition © Arjunvir Singh, The Museum of Material Memory

2. Arjunvir Singh (the researcher) with the owner of the Khes - his grandfather. © Arjunvir Singh, The Museum of Material Memory

Conceived by Aanchal Malhotra and Navdha Malhotra, this digital repository of the material culture of the Indian subcontinent primarily aims to preserve material memory infused in objects.

“Our subject matter is the small, often overlooked background of our lives — things, objects, belongings like fabrics, kitchen utensils, trunks, paan daans (boxes for keeping betel leaves), perfume bottles, sewing needles, passports, letters, postcards, paintings, dining tables, writing desks, washing cupboards, notebooks — that are not glorified or exhibited in museums, but found and still used in people’s homes,” clarifies Aanchal.

Highlighting objects in a historical context is the conventional definition of a museum but what makes this museum special, according to the co-founders, is that it also provides “a personal lens to the original owner and the memories that have been preserved within.” Conceptually this situates the Museum of Material Memory within the school of thought that prescribes the idea that a museum is a place that collects, curates and shares human experiences. Prominent art historians like Salvador Salort-Pons elaborate upon this concept, speaking of museums as spaces for empathy and as a medium that facilitates bonding. Museum of Material Memory does this and more.

%20Box%2C%20Copyright%20-%20Pavithra%20Dikshit%2C%20The%20Museum%20of%20Material%20Memory.jpg) |

|

3. Paan (Beetle-nut) Box, Tamil Nadu, India 1930s © Pavithra Dikshit, The Museum of Material Memory

4. Beaded Dogs, Assam, India late 1960s © Riya Lohia, The Museum of Material Memory

Now about six years old, this online archive invites voluntary contributions in the form of hi-resolution photographs or videos of the object with the caveat that the objects have to be from or before the 1970s. A detailed form probes and helps a layperson to start the ‘memorialization’ or the process of preserving memories of people or events, therein initiating the quest of getting to know an age-old object. The co-founders feel that “each piece requires our emotional involvement to capture as much detail as possible and achieve our vision,” but this can be challenging given that Aanchal and Navdha are solely responsible for the Museum. Also, they are both full time professionals working as an oral historian and a development professional, respectively.

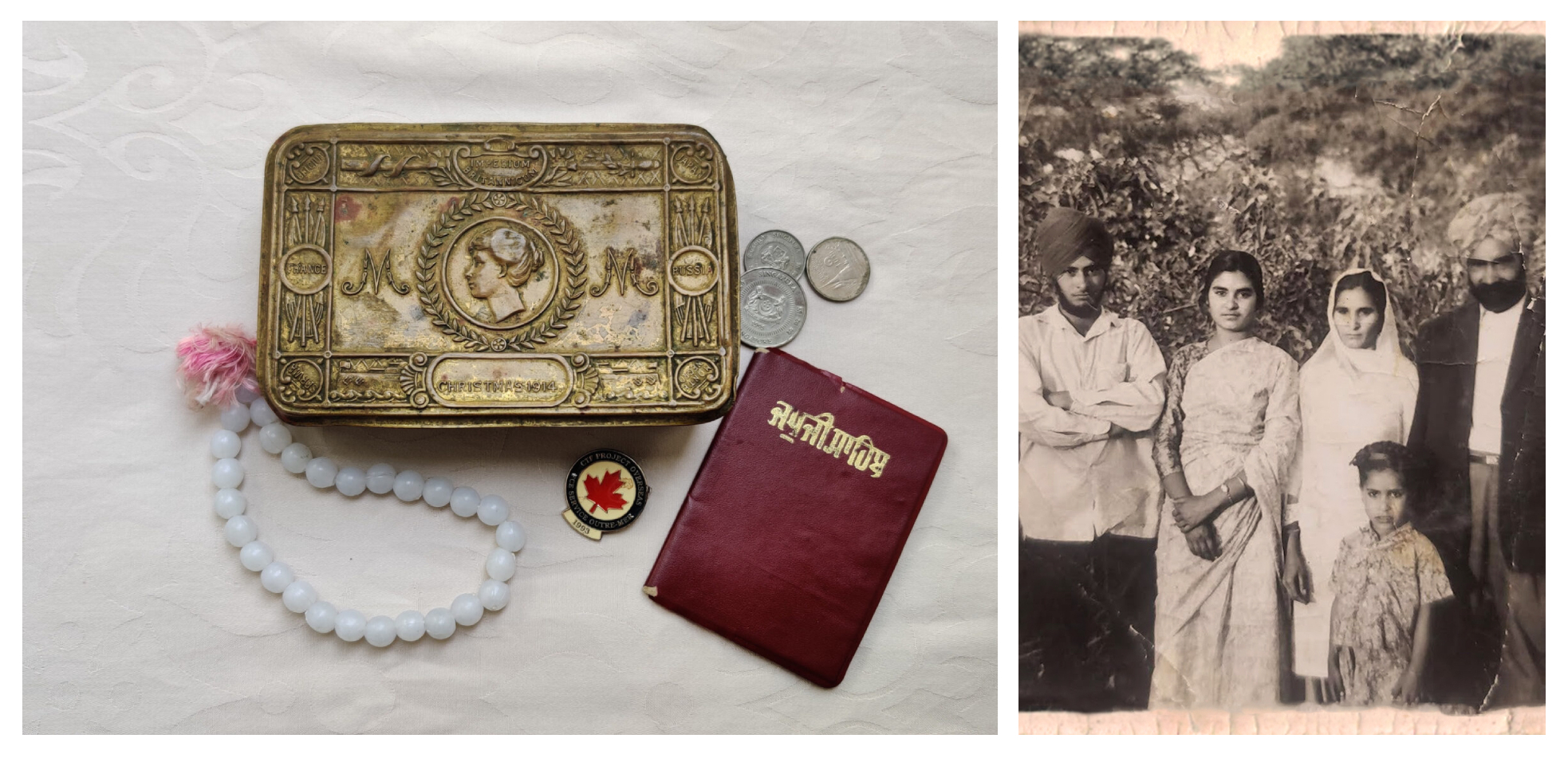

Yet, it is their shared love for objects that fuels this museum. For example, contributor Sahiba Bhatia wrote her personal history of discovering the Princess Mary’s Christmas Box given to soldiers, including Indians in the trenches of World War I, and what the object meant for the family, while Aanchal worked on the military history of the object itself.

The sustainablity of this museum does concern the duo because it is dependent upon crowdsourcing. The use of social media, Instagram in particular, to spread the word, initiate conversations and share stories with the world helps.

“Our comments section is usually peppered with people not only resonating with the object in focus, but also narrating their own family tales that revolve around similar objects. For our contributors, there is also a sense of ownership and pride,” says Navdha.

This, in turn, leads to more stories being unearthed, which feed their passion and motivation.

5. Christmas Box inherited by Jagdeesh Kaur Bhatia, presented to soldiers in trenches during World War I © Sahiba Bhatia, The Museum of Material Memory

6. Family portrait of Jagdeesh Kaur Bhatia © Sahiba Bhatia, The Museum of Material Memory

This borderless approach allows exhibits to facilitate bonding among communities thanks to memories: an object showcased in the Museum is used in homes across landscapes, which might be divided now. In practice, the immediacy of the Internet and the approachability of social media also have a downside.

“Sometimes when stories take a more political route, there can also be questions around the interpretation of the past - particularly in the case of stories on the divided history of the subcontinent, where events are remembered differently in different countries,” laments Aanchal.

“Our hope is that decades later, people can look back into the Museum and see a collective material culture take shape through the objects that populate our collection. The object is a rich ethnographic tool to understand society and culture and we hope to contribute to that ethnographic archive,” Navdha says.

The co-founders emphasize that the aim is to “activate memorializing on an organic level”: during the submission stage, through family conversations, and during the life of the digital exhibit. With each object an unheard "familial, material, social, even political” history is being told.

Uncover new stories and histories from the Indian subcontinent by visiting Museum of Material Memory.

Cover Image: Sandesh (Sweet) moulds, Rural Bengal, India Mid-19th Century © Amrita. C. Roy, The Museum of Material Memory

(This feature is based on an email interview conducted with the co-founders of the Museum of Material Memory. Aanchal Malhotra is an oral historian and writer, while Navdha Malhotra works with a social impact agency on public health and climate issues.)

About the Author:

Roli Mahajan is a freelance writer and photographer. She has worked as an editor, journalist, storyteller and development communications professional for more than a decade. She is passionate about the environment, pursuing peace and learning more about culture. She can be reached at roli.learns@gmail.com or via twitter @scholarfreak.

Similar content

deadline

15 Jan 2017

posted on

19 Aug 2013

from - to

01 Feb 2012 - 11 Jun 2012

posted on

19 May 2014