The New Face Of The Tiger

Any visitor to the 38th International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) would never escape the much-talked about new Tiger logo which was used boldly on the cover of all official publications as well as displayed prominently at all festival venues.

The new black and white logo with the Tiger looking at you in the eyes aimed to represent the festival’s new idiosyncratic and forward looking approach. This was part of a complete overhaul initiated by Rutger Wolfson who became permanent festival director this year after a stint as interim director in 2008.

With the closer integration between film screens and monitor screens, between short films and live performances, between feature films and installations, Wolfson felt traditional fringe events should be brought into the centre of the festival.

The new programme structure has been streamlined into three parts, which can each include both long and short films, art installations and live performances.

‘The new arrangement is at the same time a lot simpler and reflects the three most important qualities of this festival: discovering idiosyncratic young filmmakers, showing new and innovative work and encouraging discussion and reflection,’ said Wolfson, the 39-year-old former curator of De Vleeshal, the Dutch centre for contemporary art.

Within the new Bright Future section, VPRO Tiger Awards remained as IFFR’s flagship for discovering new talents. This competition for first and second films is always considered a launching pad of a promising career, as in the case of past Tiger winners like Love Conquers All by Tan Chui Mui and Wonderful Town by Aditya Assarat.

This year’s winners include Iranian director Ramtin Lavafipour's Be Calm And Count To Seven, Yang Ik-June's Breathless from South Korea, and Turkey's Wrong Rosary by Mahmut Fazil Coskun. A cash prize of Euros 15,000 was handed out to each winner.

If Bright Future offers a platform for talents to make their debuts, Spectrum is more for talents who have proved their mettle to return to the festival with powerful and innovative work. This year, Jia Zhangke returned with 24 City, Royston Tan with 12 Lotus and 10 Indonesian directors with their collective political memory in an omnibus film 9809, among others.

A special sidebar from Spectrum was Meet the Maestro, a project that looked at the work of Claire Denis. Her latest film 35 Rhums was premiered alongside Sun Koh’s Dirty Bitch, a short film commissioned by IFFR and inspired by a badly censored VHS of Denis’ Nenette Et Boni found in a Singapore library.

The third new section was Signals, a selection of thematic strands in the form of exhibitions and retrospectives. One novel work was the Size Matters sidebar which used three significant Rotterdam buildings as projection screens. The outdoor screenings involved three site-specific films, specially commissioned by Nanouk Leopold in cooperation with Daan Emmen, Guy Maddin with Isabella Rossellini, as well as Carlos Reygadas.

Hungry Ghosts

Inspired by Wisit Sasanatieng’s haunted-house film The Unseeable which paid tribute to Gothic horror tradition, IFFR programmer Gertjan Zuilhof created a Hungry Ghosts exhibition to offer insight into the popular genre of Asian horrors.

Zuilhof observed that the belief in ghosts by Asian viewers and makers was primarily what made Asian horrors look so dark and unpredictable than their Western remakes.

‘It apparently takes real ghosts and a real belief in ghosts to accept that a ghost will never be explained and never disappear. You can exorcise it and try to negotiate a way to live with it,’ he said.

He found the perfect location for the exhibition at the former Fotomusuem. Also the former headquarters of a daily newspaper where the old board room and print shop are still clearly visible, it was converted to a haunted house during the festival as part of the Signals section.

Six well-known filmmakers from South East Asia were invited to furnish the ghost house. In his Close Encounter of the Ghost installation, Wisit, in collaboration with set designer Saksiri Chantarangsri, built a film set for a scene in an old traditional Thai house and even recruited a ghost as extra.

Lav Diaz, well known for his extremely long films, brought his musical and visual sense to his Manila’s Dark Room. Great fear was generated by the pitch darkness in an unknown space with Filipino punk rock playing in the background. Outside the room hung haunting images of people killed for political reasons in the Philippines.

Amir Muhammad, whose political documentaries were banned in Malaysia, furnished a cosy Reading Room with Ikea furniture where visitors could sit down and read Danny Lim’s The Malaysian Book of the Undead, a special IFFR edition published by Amir.

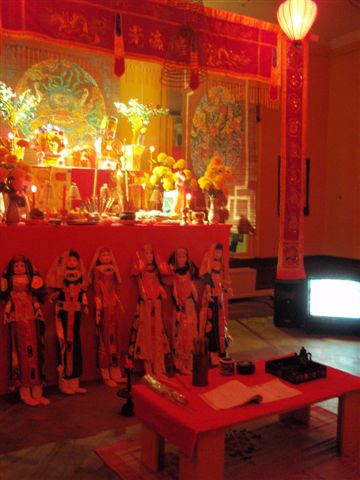

Meeting Room for Life and After-Life featured an altar, complete with all the necessary attributes from Hue, Vietnam’s old capital, as it can be seen in Nguyen Vinh Son’s film Moon At the Bottom of the Well. Recordings of real rituals, like theatrical performances, were showed on a monitor.

Transformation, Ghosts in Garin Nugroho’s House consisted of a cinema room for the screenings of three short films about ghosts that Nugroho specially made for this installation and an adjoining room with the projection of mystical Javan and Islamic texts. The rooms were decorated in the style of an old Javan house in Yogyakarta which is always associated with ghosts.

In his A Purification Pod, Riri Riza showed the preparations for the cleansing ritual of an Indonesian dagger. The installation, complete with scents, chicken blood and other sacrifices, evoked the ceremony performed all over Java by people who wished to confess their guilt to the ghosts.

Co-producing and co-financing support

IFFR has a long tradition of providing financial support to filmmakers through the Hubert Bals Fund (HBF), which is celebrating its 20th anniversary. More than 700 filmmakers from developing countries have been supported by HBF since Chen Kaige’s Life on a String became the first project to receive its support in 1989.

Although the use of Dutch coin to support international productions in developing countries has been much debated in the past couple of years, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs finally pledged its continued support to HBF before the festival kicked off. A record 33 films with HBF support were presented at IFFR this year, from Kazakhstan and Macedonia, to Chile, Thailand and China.

Another IFFR’s initiative to support international filmmakers was Cinemart, the first co-production market of its kind. Now into its 26th edition, Cinemart selected 36 projects from Asia, Europe and the US for filmmakers to present their ideas to potential financiers at the festival’s main venue De Doelen.

This year’s winners were Lance Weiler’s HIM and Byamba Sakhya’s Birdie. A total of 13 past Cinemart projects were given the opportunity to showcase their work at this year’s IFFR, including Edwin’s Blind Pig Who Wants To Fly and Fiona Copland’s The Strength of Water, both of which were in Tiger competition.

Cinemart was also the organizers for Rotterdam Lab for starting producers. Some 50 producers from around the world were gathered for an intensive five-day workshop about different aspects of production, distribution and sales. A main focus was on new distribution models and alternative ways of securing funding in the midst of the global credit crunch.

Always sandwiched between Sundance and Berlin at the beginning of the year, the next IFFR is scheduled to run from Jan 27 – Feb 7 in 2010.

By Silvia Wong

Similar content

from - to

26 Jan 2011 - 06 Feb 2011

from - to

23 Jan 2013 - 03 Feb 2013

posted on

24 May 2011

posted on

06 Feb 2012

By Kerrine Goh

28 Feb 2006

posted on

25 Nov 2013