#peripheries: Playing Medea at the Edge | Bulgaria

culture360.ASEF.org is featuring a new series of articles on the topic of #peripheries. The #peripheries have been regarded as being in the geographical margin, distant from the capital cities and cultural centres of countries. With an ongoing decentralisation trend, through this series of articles, we will look at various arts endeavours by artists, cultural professionals and art organisations who operate or occupy the peripheries in an urban society and the role that the arts play. In the second of his articles about cultural and artistic practice on the periphery, Chris Baldwin looks at a recent production of Medea by Euripides at the Ancient Theatre in Plovdiv, Bulgaria.

Something extraordinary happened in Plovdiv in June 2019, the second city of Bulgaria, situated deep in the south east of the country and close to the borders with Turkey and Greece. Euripides’ ancient play Medea was being talked about everywhere – on national television, in the streets, and in the largest Roma ghetto in Europe, Plovdiv’s Stolipinovo district, home to around fifty thousand people.

Plovdiv, the first Bulgarian city to celebrate being a European Capital of Culture, has a rich and varied programme of over 500 projects taking place throughout the year. A city at the periphery of a beautiful and complex country and at the edge of the European Union is drawing our attention to a series of questions about the nature of cultural and artistic practices on the periphery.

The Plovdiv 2019 programme draws both local and international attention not simply to spaces at the geographical periphery but also to communities at the social periphery. For this reason, Medea was being talked about everywhere this summer.

The participation of Roma, Jewish, Armenian and Bulgarian children in this major project made Medea an event, or better still a process, which will take years to digest – affecting everything from an understanding of representation of minorities and children to contested notions of nationhood and the implications for cultural policy and even the definition of what performance means.

Medea took place in the breathtaking open-air ancient Roman theatre in the middle of the city to a packed audience of three thousand people. The outdoor venue allowed for the stunning sunset and warm winds to waft over both the theatre audience and performers alike as the prologue, consisting of a teacher explaining to his large group of culturally diverse children, what had happened to Medea in the years before the action of the play. While everyone in the audience knew the plot before coming to the theatre, they were more than inquisitive to find out what this extraordinary evening might yet become. And what an event it became – both for aesthetic reasons and for what nature had in store.

Medea at Plovdiv, Bulgaria (Photo Credits: Chris Baldwin)

From the outset, Medea became the story of a woman intimately connected to all the cultural and religious diversity represented by the children of Plovdiv. As Medea’s revenge and anger grew, we were increasingly anxious when predicting who the real victims of this power game were going to be. Would they be our very own collective future as embodied by these multi-faith and no-faith children? As this question was posed to the audience, nature itself also decided to intervene and take us to the near physical breaking point. As Snezhina Petrova’s Medea stepped into the gentle theatre lights in the open-air space, real storm clouds were already gathering over the Rhodopi mountains only a few kilometers away.

Within an hour of the beginning of the performance, the heavens opened, and the biggest storm experienced in years exploded and cracked above the stage, flooding actors, children and audience alike. Yet the performance continued. It refused to be bowed. And the audience remained fixated.

Euripides made a curious decision for a Greek tragic playwright as his play was not a tragedy in the classical definition of the word. The playwright does not allow us any emotional relief from the central action of the play, by refusing us a chance to feel pity for Medea. In Greek tragedy, this is important. Rather he places the principal action, the murder of Medea’s children by her own hand, in real time, happening as we sit in front of her and, as on this evening, the storm cracked open the world above our heads seemingly punishing us all for our implicit collusion.

We were forced not just to confront the repercussions of this grotesque and unspeakable act but to witness the mechanisms of the violence against children itself. However, what was this production saying by representing the murder of children from Roma, Bulgarian, Jewish and Armenian communities? Perhaps the answer is to be found in the very structure of the project and its rehearsal process.

Medea, directed by Desislava Shpatova, and with a vibrant new Bulgarian translation by Georgi Gochev, performed by more than 40 actors, musicians and children took three years to prepare and culminated in this one single performance. In many respects, these decisions hark back to the very roots of Greek theatre as a festival and as a unique gathering unlikely to be repeated.

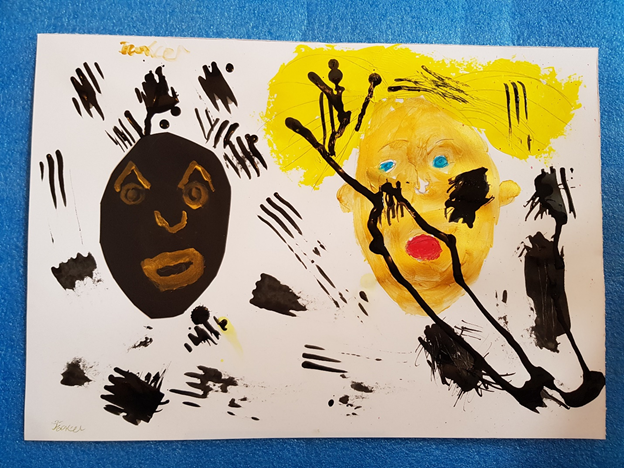

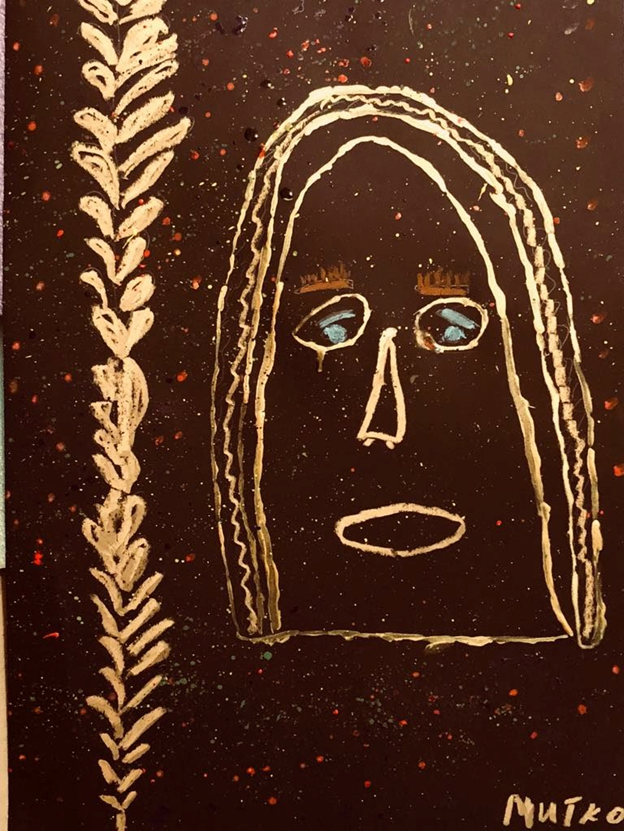

The first year of the project, as in any other first steps, were dedicated to planning and researching. The second year of work focused upon the child actors led by Alexandra Gocheva, and (again) Georgi Gochev, both psychodrama coaches, and artist Tsveti Spiridonova. It resulted in exhibitions of work by the children and professional artists, video projects, costume designs. Both acting as stepping stones to full company rehearsals, group building and deeper thematic analysis. The year was given the title ‘Field Medea’ (Teren Medea) and was presented as a series of events and exhibition at the National Gallery in Sofia.

Artwork by children actors (Photo Credits: Legal Art Centre)

In this way, the voices of the Roma children and other minority communities moved from the periphery to the centre for a few critical hours – their voices and insights were given central focus by and with artists in dialogue. In a society so divided, so scared about the nature and consequences of the voices of its minorities and in particular, voices of children, this production can perhaps be considered to have been a radical moment for the voices of Bulgaria’s powerless to gain centre stage.

Artwork by children actors (Photo Credits: Legal Art Centre)

Telling Medea requires us to make choices, just as it did for Euripides. It was Euripides, after all, who introduced into the already existing story, the act of Medea killing her own children. In this Medea, we are told the story of the migrant, the refugee, the person who lives in an unknown and hostile world. It is also about children. But it is also the story of a woman who searches for justice and revenge through her own actions and not though the state or the courts, a woman abandoned by society and its ‘noble’ institutions is driven to madness. But she does not die at the end of the play. She enters victorious, triumphant.

Medea at Plovdiv, Bulgaria (Photo Credit: Chris Baldwin)

This might be the crime we find most hard to forgive, even two thousand years after the play was first heard and seen. The voice of this woman, and of these children, moved from the periphery to the centre, impacting both politically and aesthetically in this hypernatural space. With the help of the storm, its thunder, rain and lightning, this antique story and its radical casting, any sense of normality for all those present was obliterated.

This article is written by, Dr. Chris Baldwin (www.chrisbaldwin.eu), who was the Creative Director of Galway (Ireland) European Capital of Culture 2020 and Curator for Interdisciplinary Performance for Wroclaw (Poland) European Capital of Culture 2016. His new book on citizen-centred dramaturgy and collective trauma will be published by Routledge in 2020.

Useful Links:

Teren Medea: https://plovdiv2019.eu/en/events/1618-opening-of-the-exhibition-teren-medea-20-may-16-june-2019

On Roma and Plovdiv: https://yomadic.com/stolipinovo-gypsy-ghetto/

Similar content

posted on

14 May 2019