Poets as Keepers of Buddhist Tradition: The Zare Culture of Myanmar, Thailand and Yunnan

As part of culture360's ongoing Call for articles 2023, Bikash K. Bhattacharya writes about a unique poetic tradition in the Theravada Shan communities of upper Myanmar, northern Thailand and the Yunnan province of China, that serves as a primary means of transmitting the Buddhism teachings.

An Erudite Poetic Tradition

Known as the ‘doctrine of the elders’, Theravada Buddhism is the oldest form of Buddhism that is believed by its followers to have remained closest to the original teachings of the Buddha. In Theravada Buddhist societies of South and Southeast Asia, where this school of Buddhism is predominant, the monks are the primary transmitters of Buddhist teachings (dhamma). However, among the Theravada Shan communities—who refer to themselves as Tai—inhabiting in upper Myanmar, northern Thailand and parts of Yunnan in China, there is a distinct group of lay poet-reciters known as zare, who transmit the complex Buddhist teachings through an elaborate form of poetry dating back to the sixteenth century. Known as lik long (great writing), this form of poetry is composed and recited by zares, who are predominantly lay Buddhists, in temples and houses on special occasions. The lik long texts are primarily Shan language poetic rendering of jatakas (the birth stories of the Buddha), suttas (discourses) from the Tipiṭaka, as the Theravada canon is popularly known. Lik long texts are embedded in layers of Shan cultural interpretations of the Buddhist teachings and at times include extra-canonical topics.

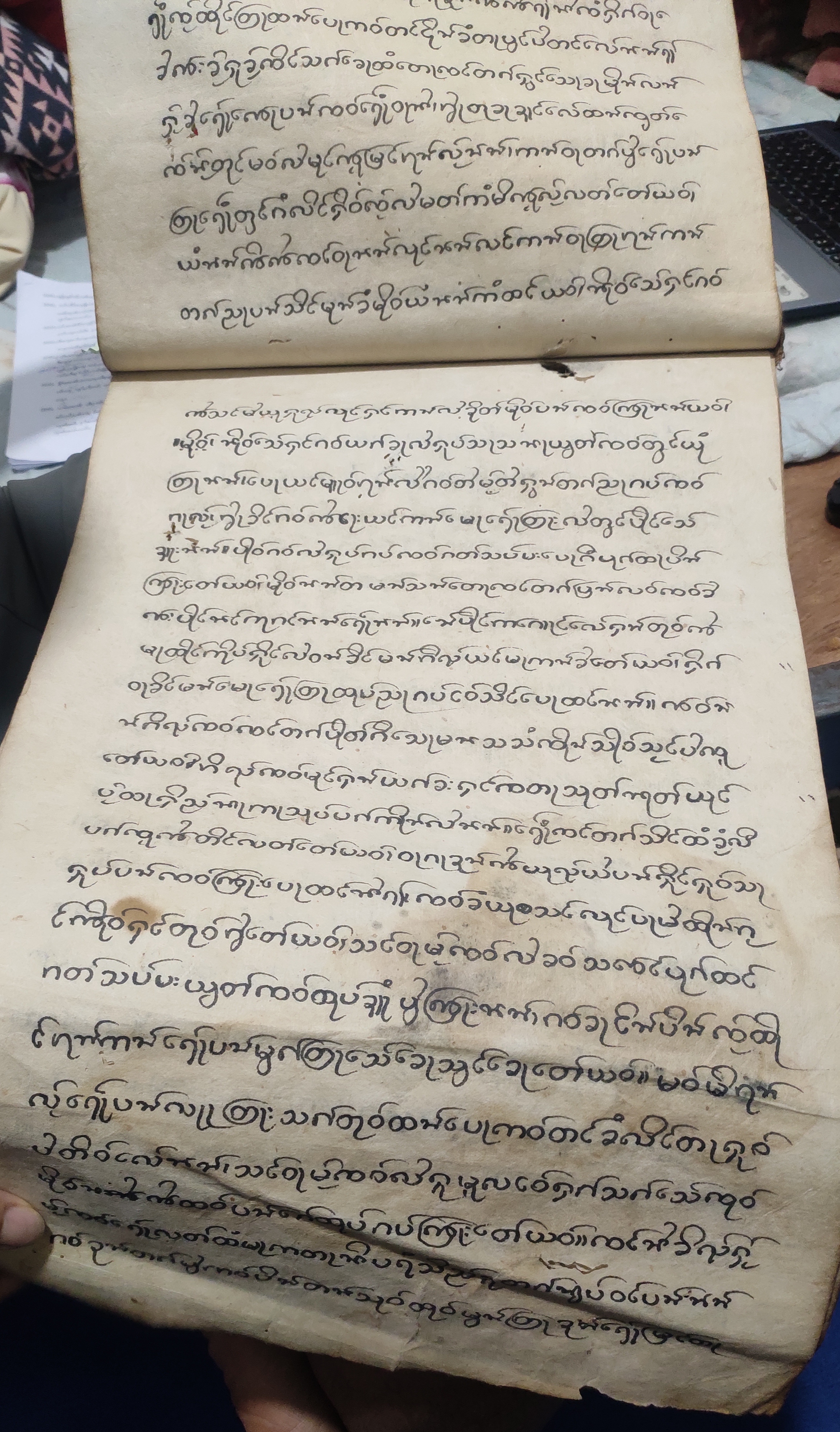

1. An old lik long manuscript preserved in the Centre for Manuscript Studies, Shan State Buddhist University, Taunggyi, Myanmar. © Bikash K. Bhattacharya

Traditionally, poetry has been an important aspect of Shan culture. Mrs. Leslie Milne (1860-1932), one of the first anthropologists to write about the Shan and to have lived among them in the early 1900s in Hsipaw and Hsenwi in the present-day Northern Shan State of Myanmar, noted in her book The Shans at Home (1910) that there was a popular custom of rhyming competitions among the Shans, at which groups of women spar with groups of men, exchanging witty repartee in spontaneously composed rhyming verses.

Originally, the term zare referred to the secretary of a zaopha, a Shan ruler. Later, the meaning of the word extended to include poets and poetic reciters of Buddhism-related texts, writes Kate Crosby and Jotika Khur-Yearn, a professor of Buddhist Studies at King’s College London and an expert on Shan culture at School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London, respectively. Among the six most famous zares of all time, four of the five men held high office in the palace of one or the other Shan ruler, including one marrying into a royal family, which hints at the high status of a zare in the past. The earliest well-known lik long poet is Zao Thammatinna (1541-1640 CE).

In 2022, this author spent almost a year learning Pali alongside zares at Shan State Buddhist University in Taunggyi, the biggest city in Myanmar’s Southern Shan State. Although zares compose lik long texts in Shan, knowledge of Pali and Burmese languages is crucial for them as they deal not only with topics from the Pali canon but also from Burmese commentaries (nissaya) on the Theravada canon. Sai Hla Tun, 72, a senior zare from Keng Tung in Southern Shan State, said that without the knowledge of Pali and Burmese, one would not understand the discourses of the Tipiṭaka, which is the basis of nearly all lik long texts.

The key occasions in which zares are invited to recite lik long are during the building of a new house, novice ordination ceremonies, death commemorations and the ‘temple sleeping’ (kam-sil non-kyaung) ceremonies, when lay people spend a period of time engaged in religious activities at the local temple, with funerals being the most important occasion for a zare. While attending a Shan funeral at Namkham in Northern Shan State in October 2022, Sai Jom Hlaing Han, the local zare reciting lik long in the house of the deceased, told this author that funerals are special occasions because in these events the zare’s craft helps people cope with bereavement. “In funerals, it is not just about reciting lik long. The zare needs to be able to dig out or compose a lik long text that is suitable to the situation of loss. The text should help the mourning audience cope with the loss and drive home the key Buddhist teachings of impermanence (aniccha) and suffering (dukkha) as essential aspects of the universe.”

2. Zare Sai Jom Hlaing Han reciting lik long poetry in a Shan funeral, with the family members of the deceased and elderly villagers listening to the recitation and paying homage to the altar of the Buddha in Namkham, Northern Shan State, Myanmar. © Bikash K. Bhattacharya

Sai Line, a zare from Mu-Se in Northern Shan State, said that the most important thing a zare needs to have is parami (perfection), the Buddhist ideals such as generosity, patience and wisdom. “Only when a zare is able to cultivate parami, can he or she expect to compose better lik long texts.”

Zares learn and hone their craft in Shan Buddhist monasteries over a span of several years. Both Sai Jom Hlaing Han and Sai Line, like many other zares currently working in Mu-Se and Ruili—the two adjacent border towns in Myanmar and China, respectively—trained in the art of zare in Mohnyin, a town in the Kachin State with a substantial number of Shan Buddhists, known for its heritage of meditation in the Ledi tradition.

A Unique Repository of Women’s History

Albeit being a heavily male-dominated tradition, the lik long poetry is not an exclusive domain of men. One of the six famous zares of all time is Nang Kham Ku (1853-1918), the daughter of a prominent zare and former monk, Zao Kang Suea, who himself trained her in the craft of composing lik long poetry.

Moreover, a peculiar aspect of lik long texts is that each work contains elaborate information on the sponsors patronising the composition of the text. As a significant number of the sponsors are female, a sizable corpus of lik long texts contain personal and social histories of Shan Buddhist women. Thus, lik long texts are a unique source of a less visible and subaltern subject neglected in mainstream Burmese, Thai or Chinese historiographies: the Shan Buddhist women.

A Tradition Pushed to the Margin

Khammai Dhammasami, the leading Shan scholar monk and founder rector of Shan State Buddhist University in Taunggyi, says that in the past, Shan monastic education both for monks and laity heavily centred around learning lik long literature. Later, as Shan Buddhist monastic examination boards emerged, these institutions did not incorporate lik long literature, and inadvertently contributed in pushing this Shan poetic tradition into the margin.

With the formerly independent Shan states ruled by zaophas integrating into the three modern nation states, Myanmar, Thailand and China, the Shans became a minority dominated by Burmese, Thai or Chinese literary cultural forms, the zare tradition significantly diminished and lost its previous status.

3. Sai Line, a zare based in Mu-Se, Northern Shan State, reciting a lik long text composed about a hundred years ago. © Bikash K. Bhattacharya

Sai Line, the zare from Mu-Se, says that sometimes people tend to look down upon zares as mere “hired reciters” not knowing that lik long compositions and recitations have been an essential element of Shan Buddhist literary identity for centuries.

The silver lining however, is that Shan State Buddhist University in Taunggyi has a vibrant ‘Centre for Manuscript Studies’, primarily working on Shan lik long manuscripts. In addition, the university has also established a Bachelor’s Degree programme in 2020, aiming to help the zare tradition thrive and obtain scholarly attention by focusing on the academic study of lik long texts.

Cover Image: Zare Sai Jom Hlaing Han reciting lik long poetry in a Shan funeral, with the family members of the deceased and elderly villagers listening to the recitation and paying homage to the altar of the Buddha in Namkham, Northern Shan State, Myanmar. © Bikash K. Bhattacharya

About the Author

Bikash K. Bhattacharya is an incoming graduate student of anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin from fall 2023. His research interests include anthropology of religion, translation, Buddhism and Christianity on the Indo-Burma borderlands.

Similar content

14 Jun 2019 - 26 Jan 2020

from - to

25 Oct 2011 - 04 Dec 2011

12 Feb 2016 - 14 Aug 2016

posted on

05 Jul 2011

from - to

15 Apr 2011 - 05 Feb 2012

posted on

02 Oct 2018