Search for Dance: a conversation with Takako Suzuki

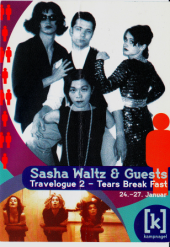

[caption id="attachment_2352" align="alignright" width="170" caption="Tears Breakfast (production 1994)"]

[/caption]

[/caption]Berlin, Germany

“I don’t want to be stranger in Germany,” declares Japanese contemporary dancer, Takako Suzuki, in one of our kitchen conversations in the trendy Berlin-Prenzlauerberg neighbourhood. The Nara-born performer is a familiar face on stage both in Berlin and the international arena, having worked with Germany’s premiere dance company, Sasha Waltz & Guest from its early beginnings in the 90s. She continues in a very calm and level-headed manner, “I wouldn’t use stereotypes. This is so out. Nor do I want to be labelled as Japanese, or Asian. I don’t want to be “kawai” (‘cute’ in Japanese).

This discussion stems from shared, daily realities that are faced by those who choose to lead life beyond the borders of culture with a take on the combination of factors such as being Asian in Europe, as an independent woman in pursuit of passion for one’s art. As a local-foreigner myself, living and working in a similar environment, I can relate to Takako through a continuous process of discerning the complexities of language and perception, vernacular to the other.

Takako recalls an instance at Dock 11 , while improvising on the street, “Crossing between the pavement and the tram tracks, I put my sunglasses on and as I strutted using my movement – people passing were screaming, ‘Yoko Ono!’” It may be flattering to be taken as the glamorous widow of John Lennon but it is almost the same as being greeted ‘Konnichiwa’ or ‘Ni Hao’, with an assumption that all Asians look the same. How can one deal with the concept of uniformity in seeing Asians in the land where our gamine features seem to stand out? How can one understand the way of thinking other than one’s own? Is it essential to wear the flag of nations when we have already built our homes in a place considerably outside our zone? The questions I’m posting aspire to lead toward multi-directional paths rather than a one-way criticism.

Even I, in the role of spectator and participant, in reference to daily life and the real stage in the performing arts, I cannot help but pay extra attention to Asian artists particularly if they are working with a Western theatre or dance company.

The 44-year old butoh-trained woman, who invested on learning German in Japan prior to her move in 1991, tells “In Tokyo, I met different Japanese people who spent a long time in Europe and America. They exuded a feeling with a bit of arrogance, I come from outside. And then when I moved here, everyday, I have had to confront where I come from. I had to learn the mentality and think inside-out.”

“I remember the first time I arrived in the S-bahn station, Oranienburgerstrasse. I was looking for Tacheles , but there was no street name or sign. Coming from a neon city, it was impossible for me to see in the darkness. There was such a huge contrast between Berlin and Tokyo. I could only see German people.”

“Before I turned 30, I lost my dance master. I couldn’t find a partner (dance), I felt so alone. No one was waiting for me to continue dancing but I really love dance,” utters Takako. After completing her design degree in Tokyo, Takako started dancing at the age of 21 and trained with the 3rd generation of Butoh Ajimaro (master), Anzu Furukawa. “Anzu took me to Germany with the company of 4 dancers for a month in Freiburg in 1986. We got a space in a factory. These things I never knew in my life. I was quite shocked with the possibility. I couldn’t believe that people, dancers can take off for a month just to dance. After that I continued to work as a designer in Tokyo. But I was sure that I liked the way of life in Europe.”

“Then there was the choice,” she elaborates, “I felt that I have to be responsible for my life. Dancing was like a choice between life or death. In Tokyo, you cannot just survive by becoming a waitress. As I grew up in a comfortable family, I wanted to dance but couldn’t live this life. My father was likewise not in favour of this, since I already had regular job. One day, he came to meet my teacher. He wanted to check out this woman who to his mind took his daughter away from the normality of living. He knelt in front of my teacher telling her not to take me in. And in Japan, when someone kneels down, this is to be taken seriously.”

“You ought to note that in the end of 70s and 80s, butoh performers survived by living a communal lifestyle whereby “earning shows ” provided the collective means to continue dancing. The question of how to live on dance was lingering in my mind. I was kicked out from the company because I was questioning things. I took the challenge of my master of taking on the lifestyle that they have chosen together. I gave myself 15 days – and I learned much more about life in this short period of time.”

“Dance offered a different opportunity. Butoh was about becoming free from the concept of nakedness. Apart from my love of dance, the experience of running in front of Meiji Emperor shrine naked in Tokyo being chased by the police was truly exciting as young dancer- at least at that time. Imagine being dressed only in gold body make-up?”

“When I pursued dance, I had zero money. I had to ask my best friend for 120Y to take the train. I looked for people to work with me in Japan and then later took on a regular job so I could afford to dance at least on weekends. Rosas came to Japan and I took the workshop. Since I was working, I had money and can pay for the workshop.”

“In the process of fulfilling my dream, I moved to Germany initially for half a year and came back in 1992. I figured that there would be a problem with visa so I used my design studies to get into Universitaet der Kuenste (Art Academy). In July 1992, I became a student once again. But I already studied. I wanted to continue dancing. I went to a lot of courses, looking for someone interesting. Sasha Waltz just came back to Germany at that time and met her at a dance class. I did the show with her for Lindy Annis called Paternoster, a production in Rathaus Schoeneberg. We were 10 dancers. What was interesting was that she let us develop our own movement. I liked her a lot as I understood her communication process. When she said ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to a specific movement - it was clear why.”

The original Sasha Waltz& Guest company member declares, “When I met Sasha Waltz, it was real dialogue.” It was a great timing for Takako, who was on a quest to find her path in dance. Since the post-Berlin wall project, the Japanese dancer continued to work with the German choreographer. The island child discovered the differences in the ways of doing things coming from an orientation of master-student relation in Japan shifting to an environment of collaboration in Germany.

“In Japan, it’s clear who is the boss or the assistant. But if someone gets tried, someone has to take over. Through my work in Germany, I somehow understood the way of thinking and how people approach their independent agenda. There is a manner that one can read the underlying message that “I organise everything – it’s my company” whereby the demarcation line between professional and personal relationship is clearly defined. I was totally shocked with this approach and eventually decided for myself that my interest in someone’s work is just about that.”

Takako, who happened to be the youngest and smallest company member of Sasha Waltz & Guests when it was first established enjoyed the benefits of being treated as such. When asked to choose a sentence for an improvisation piece, she borrowed Breton’s quote on Frida Kahlo as a reflection of her own experience “She’s like a ribbon tied to a bomb.” This time she acknowledged and embraced how different communication was even in the language of dance.

At the end of our meeting, she says, “When you are in Asia, in Japan to be more specific, you cannot understand the reaction surrounding you, and how this can influence you. There is not one law that applies to all. You will not know this before you come to Europe.”

Photo credit:

Tears Breakfast (production 1994), Nasser-Martin Gousset (France), Akos Hargitay (Hungary), Takako Suzuki (Japan) and Sasha Waltz (Germany).

Vanini Belarmino is the performiing arts Asia contributor for culture360.org. A Berlin-based producer and curator specialising in interdisciplinary exchange and cross-border collaborations, she is the Founder and Managing Director of Belarmino&Partners, an international project management and promotions consultancy for arts and culture.