The role of cultural heritage within cities

As part of culture360's ongoing Call for articles 2023, Jenny Siung looks at the role of cultural heritage within the context of cities, focusing particularly on current issues that are emerging post-pandemic; migration, the role of cultural heritage in fostering understanding of communities; sustainability and health and wellbeing.

When reading Museum 2040 published by the American Alliance of Museums in 2018, they looked into the future and projected how museums would operate in 22 years’ time; museums would become fluid, dynamic and community centred institutions. This aspirational transformation occurred 3 years earlier with the global outbreak of Covid-19, a pandemic that upturned life globally, including the arts, cultural and heritage sectors. For the first time in many years, these organisations lost contact with their audiences and had to quickly respond to a situation that was both unpredictable and unknown. A number of other crises emerged; the Global North and South faced food shortages, cities became ghost towns overnight due to lockdowns, the murder of George Floyd in the USA gave rise to Black Lives Matter and a wave of anti-Asian sentiment occurred with finger pointing to the origins of the Covid-19 virus. For a while, it seemed the lights went out worldwide.

Yet creativity loves a good crisis.

The arts, cultural and heritage traditionally are located in cities rather than in isolated places. They can have an effect in the surrounding area and communities, otherwise known as a spillover. This is understood to be a process by which an activity in one area has a subsequent broader impact on places, society or the economy through the overflow of concepts, ideas, skills, knowledge and different types of capital. The pandemic spurned a multitude of spillovers worldwide. These are a few examples.

Art Galleries - serving local communities

Firstsite Gallery in Colchester, Essex UK, with a population of over 120,000, calculated one in five children live in poverty, which has subsequently increased since the cost of living crisis. The gallery addressed food poverty in 2018 offering hot meals for families during holidays for free, coupled with art activities and still continues today. During the pandemic, the gallery produced Art is where the home is art packs with input from well-known contemporary artists and mailed them out to families. Firstsite became a ‘frontline’ gallery for its local community living in both isolation and deprivation (the term frontline became synonymous with health workers in hospitals dealing with patients during the pandemic).

1. Firstsite Gallery Colchester, Art is where the home is art packs © Firstsite Gallery Colchester, UK

Outdoor Spaces

The transformation of outdoor spaces for people to gather is an example of spillover in cities. Most cities can cater for outdoor dining as well as arts and cultural events. Ireland is an exception renowned for its rain, yet businesses changed the way we engage with our public spaces. Areas of the city centre in Dublin transformed into shared spaces for cafes, restaurants and bars. The Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA), Dublin reacted to pandemic-related lockdowns by turning its 48 acres of land into an outdoor space offering art workshops, talks, music performances, art installations. IMMA Outdoors responded to the-then public’s appetite to meet and socialise outdoors and based on its success, the programme has become a key focus for the museum.

Museum as places sharing empathy, fear and joy

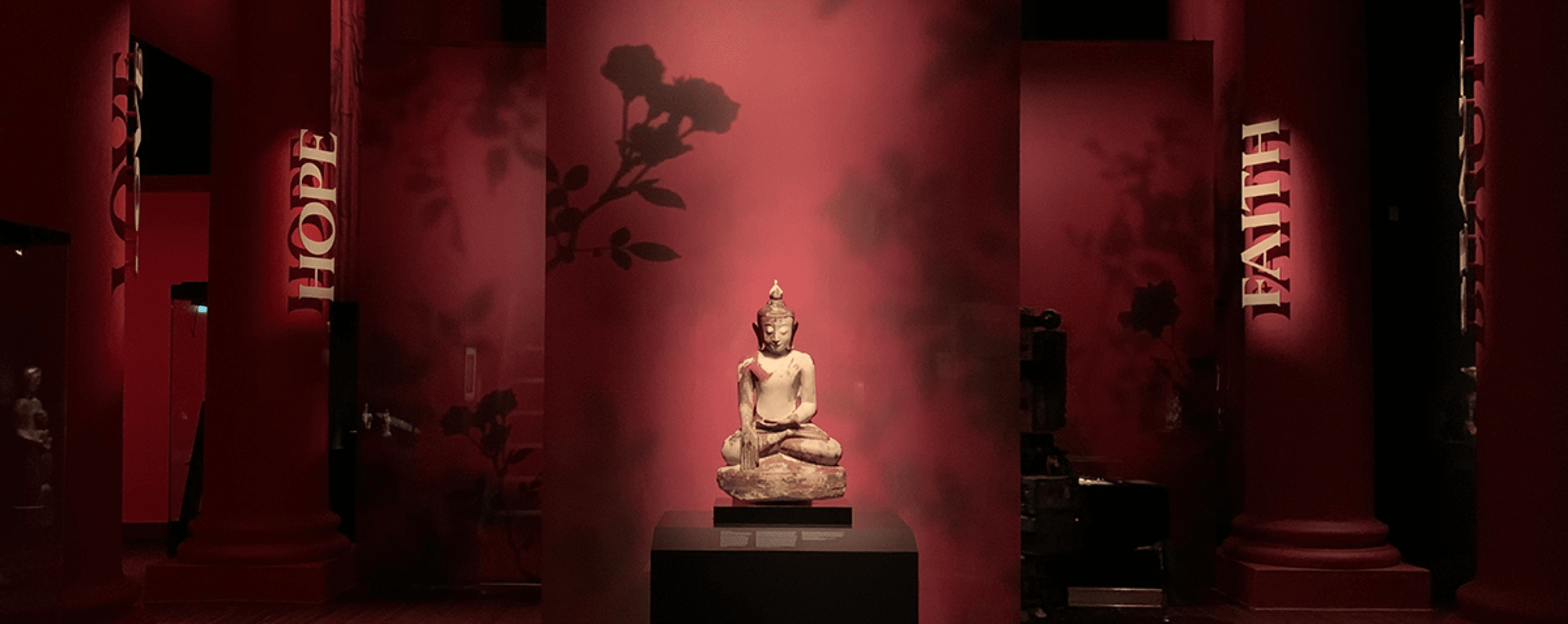

In 2021, the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore invited staff to select objects from its collection for its exhibition Faith Beauty Love Hope – Our Stories. Visitors experienced a more ‘human’ side to the museum as a means to remedy the hardships of the pandemic and touched on a number of emotions, including empathy, fear and joy. Members of Singapore’s interreligious community were invited to select faith-based objects and what it meant to them in the context of their faith and practice within the local community.

2. Asian Civilisations Museum, Faith Beauty Love Hope © ACM Singapore

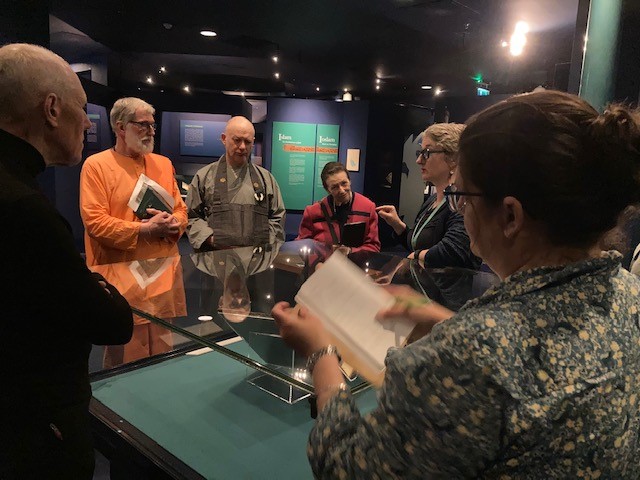

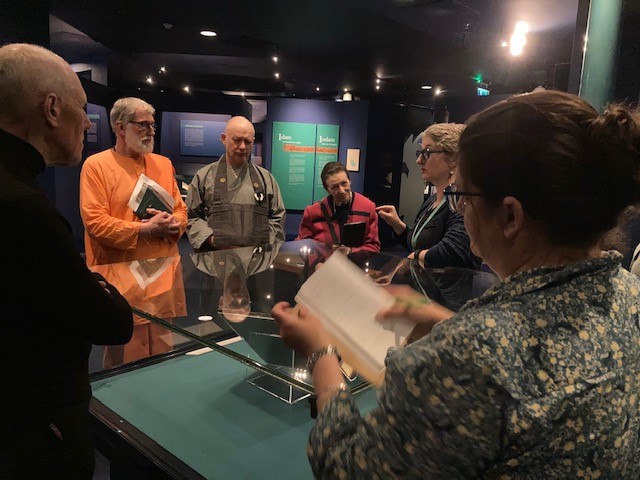

This emotionally-inspired exhibition encouraged this author a year later to invite members of a Dublin interfaith-based community to respond to faith objects from the Chester Beatty collection in a project Faiths in Focus. Videos of the members responding to the museum collection will be made available online. By opening up these perceived closed spaces, arts, cultural and heritage can provide a safe environment for co-creation, dialogue and exchange.

3. Chester Beatty, Faiths in Focus © The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Ireland

Cultural Heritage - models for hybrid engagement

The pandemic accelerated a digital ‘reboot’ for the arts, cultural and heritage sectors in a rapid transformation from onsite to online engagement. The National Heritage Board (Singapore) was forced to rethink how best to create access for audiences during restrictive lockdowns. A virtual trail was developed and piloted on the history of World War II in Singapore for a local school catering for children with learning needs. Students were provided pre-recorded videos with a follow-up of live interactive content while they walked around the historical sites adhering to the then-pandemic restrictions. The hybrid or blended model of onsite and online engagement is widely being used by the arts, cultural and heritage sectors today.

Reboot, reflect and take responsibility

These examples reflect the innovative, dynamic and creative skill-sets of our colleagues in the arts, cultural and heritage sectors. As reflected by the American Alliance of Museums, organisations were forced to reboot, reflect and take responsibility as a result of the global pandemic in how they engage and serve their communities. The lessons learned and fluid, dynamic, community centred approach will undoubtedly be applied to the current and more long-term challenges we face as a global community today: climate change, the forced migration of people from the Global South to the Global North as well as the repatriation of cultural objects.

Cover Image: Chester Beatty, Faiths in Focus © The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Ireland

References for further reading

Rozan, Adam, ‘Hello and Welcome to the Future’, Museum, 2040, November-December issue, volumes 96, no. 6, 2017, American Alliance of Museums, p.17

Fleming, Tom, Cultural and Creative Spillovers in Europe: Report on a preliminary evidence review, October 2015, Arts Council UK, Arts Council Ireland, Creative England UK, European Centre for Creative Economy Germany, European Cultural Foundation Netherlands, European Creative Business Network, pp. 4 and 14-15

About the Author

Jenny Siung is a specialist in intercultural dialogue and on engagement with Islamic, Asian, East Asian, and European religious and artistic collections. She has led and co-developed collaborative learning programmes both in Ireland and internationally. An ICOM CECA Best Practice Award in Education winner (2017), she works closely with makers and museums on questions of Irish national cultural identity, decolonisation of museum learning as well as cultural diversity, creativity and critical thinking for teachers and schools.

She has worked with boards and foundations including EU Erasmus +, Religion, Collections and Heritage Group, Asia Europe Museum Network, Learning and Education Group and Anna Lindh Foundation.

Similar content

30 Oct 2018 - 30 Oct 2018

11 Feb 2016 - 12 Feb 2016

posted on

28 Mar 2012