The seer and the seen: challenges faced by artmakers in the age of AI

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been one of the many buzzwords in recent years and is increasingly prevalent in every facet of our society, including the cultural and creative sector. While the boundaries of AI models remain unknown to us, it is already clear that AI is here to stay and it is therefore of utmost importance that those in the sector work towards being creative in responding to and using AI and technology.

In a series of 2 articles, Dr Bridget Tracy Tan takes us through what is emerging on the cultural horizon for artists and cultural professionals in the area of AI. In the second article, we explore what opportunities and challenges AI presents to the cultural and creative sector.

“And in this instance, you who are the father of letters, from a paternal love of your own children have been led to attribute to them a quality which they cannot have; for this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners' souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.”

Socrates, in conversation with Phaedrus, on the invention of writing, Plato’s Phaedrus, 257c–279c, Cooper, J.M. and Hutchinson, D.S. (1997). Plato: Complete works. Indianapolis, Ind.: Hackett Publishing Company

When writing was regarded as inferior to actively memorising

It is worth noting that ‘writing’, when first innovated, was frowned upon as encouraging rote learning without true understanding. Text as mechanical record was seen as inferior to human memory and elocution. The analogy can apply today with data in neural networks in machine learning and deep learning, artificial intelligence (AI) programmed to mimic the human brain and its processes. If clouds today can store big data while the digital realm draws down and processes those as communication of ideas in ‘art’, then this might also resemble a kind of rote that eschews true understanding.

The role of the author and to whom the rights belong

One of the fundamental challenges that artmakers face in the age of AI and digital art is the concept of authorship. Authorship as it pertains to the physical human creator, a body or a being that has administered himself or herself in the act of creating. As recent as 6 September 2023, an artwork involving the use of AI was denied copyright protection in the USA.1 World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) has also indicated in general, that the copyright of art creations only applies to one involving a ‘human author’ in its making.2 Elsewhere, the concept of digital access and AI generation have been pivotal disagreements manifesting as strikes by the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA).

The key question remains: if ‘digital mimicry’ 3 is easily accessible and conveniently reproduceable at scale, why would we need humans at all?

Many studies have been conducted to examine the comparable advantages between the human brain and that of the computer – that is, loosely put, AI incarnated. In short, the human brain champions Lotfi Zadeh’s 1965 ‘fuzzy logic’4 with its ability to absorb multimodal information and respond with variable sensibilities in judgment and emotion or imagination for example. AI however, continues to require volumes of data and paradigms, accruing insensible quanta of such, rendering outcomes in parity with what has been measurably stowed.5 The human brain outperforms AI in almost all aspects, except that of speed. In the processes and production of art, speed is likely an advantage, since faster means volume, and volume invariably means revenue, gains and more room to grow.

Digital content creation and how it impacts artistic practice

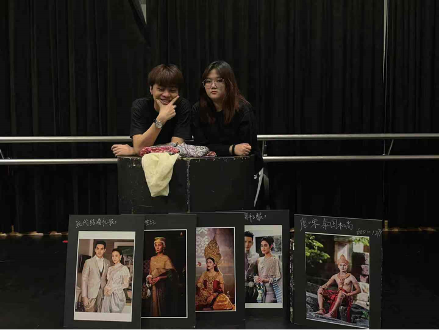

In 2021, shortly after the recent pandemic had dissipated, students from the Theatre (Mandarin drama) programme at Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) performed a graded project presentation, articulating content in the format of Douyin. Douyin is the exclusive, mainland equivalent of the international version we all know as TikTok. The students were studying a module that drew inspiration from Southeast Asian iconography in the Kingdom of Ayutthaya, Siam, invoking a ‘retelling’ of history through modern eyes.

This module ran for a semester, alongside mandatory research of the specific history of Ayutthaya. Students had to digest the content in a short space of time as well as adapt it to their practice in the module. For the students however, conveying idioms and historical narratives culturally dissimilar to theirs seemed inauthentic. Instead, they invoked contemporary culture, using Douyin ‘live’ as a platform, sharing the learned experiences and content as a lifestyle show. As Theatre students, they engaged in actor training. Douyin is very much like theatre. It involves live action with a greater degree of dynamism than scripted television that is asynchronous in production and invariably edited for continuity. Employing Douyin as a genre, they incorporated another layer, to showcase costumed, television actors in a well-known modern serial set in the reign of Ayutthaya.6

1. Students acting as presenters in a Douyin ‘live’ stream with studio photos of the costumes worn by television actors for บุพเพสันนิวาส or‘Love Destiny’, a famous television serial set in the Kingdom of Ayutthaya7 © NAFA

From the start, Douyin has been differentiated from TikTok. The former focuses more on self-improvement and education while the latter is more to showcase 'artistry' and provide entertainment.8 The fact that the students elected to use the Douyin paradigm speaks volumes. Content that is specifically created for the mainland, and not for audiences beyond; content that is generated by locals for locals and does not involve outside agents in the process or production.

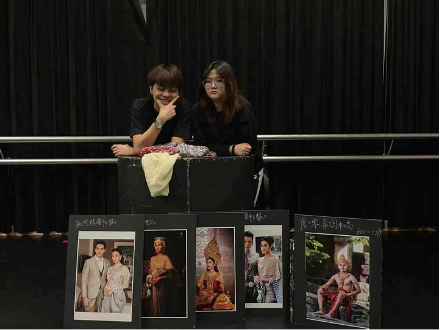

In this example, the students were astute to utilise Douyin as a paradigm of ‘self-improvement’ and ‘education’. The platform is synonymous with a veracity of content design for positive gain. The actors proffer consumption of the content as universally for youth. They evaluate their learning journey as mirrored in the preference by local youths as well, through the television serial. They even added a commercial break, and inserted a ‘crab dance’, a Thai invention (that was unrelated to the topic in the current syllabi) on social media that gained more fame when improvised online by famous Korean pop group, BLACKPINK.

Critical art: acknowledging the difference between digital fictions and real life

Their performance was ultimately a type of metafiction. Metafiction is a paradigm that constantly reminds us that we are looking at ‘fiction’. It is a fiction of a fiction as it were. In this process and performance, the result is renewed consciousness, for both the content itself and the format, but also of the platform. This consciousness extends beyond the social, to the cultural as well.

The students remind us they are purveyors of what exists as the documented history they are taught, through sources that include what has been portrayed in the television serial. There is no attempt to tout authenticity, didacticism or ‘truth’. They concede they are unable to fully process what they are being taught in the brevity of the module’s duration. There is something uniquely self-critical in the review of their performance as Douyin ‘live’. This pseudo-parody is only possible involving sentient humans, in a self-conscious articulation of the artistic presentation expected of the module.

2. Students acting as presenters in a Douyin ‘live’ stream performing the crab dance as a commercial break9 © NAFA

The meaningful use of AI and digital tools in artistic practice

In the advent of digital art and AI, content creation skates a fine line between what is real and what might not be. In the case of live streaming and digital communications, there is also the issue of veracity, consent, and propriety. These elements directly correlate with morals. The moral obligation and moral accountability that society and its agents bear or should bear as information and data are rapidly spread, used, and re-used, in a larger collage of digital arts and culture.

In January 2023, a class action lawsuit was filed by illustrators against AI companies to claim copyright interests they asserted were rightfully due to them.10

With big data available, AI based technology such as the now well-known ChatGPT and others like it, have developed capabilities that are borderless in tapping on what is available, irrespective of rights and interests of artistic products created by human hands alone. Because the technology itself has proprietary interests, it is also challenging for technology owners to divulge how they might work around programming and possibly avoid infringement.

Art institutions are likely already providing education and discourse on the matter of authorship and rights. It is timely to rethink how rights and authorship are conceived, in the wider ambit of creative collaboration involving multiple resources, big data and humans alike. While it is not possible to know and teach every element and aspect involved in the wake of AI and the digital arts realm, art schools should not merely showcase what AI can achieve as a spectacle or as a thrill. There should be a concerted effort to benchmark technology for its capabilities that complement rather than merely augment or replace human intelligence.

As early as 2021, Unity China facilitated an exhibition of Media Architecture students from NYU Shanghai.11 The work by one pair of students was described as having “..used a series of interrelating, co-moving orbits to capture ‘the gentle yet profound - intangible, yet inseparable way in which the self and the universe interact and influence one another.’” Additionally, “Their project, titled 天行有常, was inspired by the wisdom chronicled in the ancient philosophical manual of I Ching (易经), also known as the “Book of Changes.”” 12 In this alone, we can understand that students were not merely learning how to operate technology, but conceptually underpinning their own relationship to their creative endeavours, their humanity, to the rise and the potential of technology in an expansive dialogue of criticality.

Establishing authorship, evolving collaboration and new knowledge

In many ways, AI can be a useful tool to support creative endeavours and even reimagine the course of arts, both in production and in practice. But the use of AI in creative work invariably raises questions of substantive authorship and by that token, substantive knowledge. In the case of copyright denied on September 6, the author had claimed to have contributed numerous “inputs” and “revisions” in generative AI employed before his artwork was ‘birthed’. The authorities acknowledged authorship and requested the author to exclude parts generated AI as a condition of granting the copyright. But the author refused.

The history of art has long examined objects that were created by humans for humans. An appreciation of the ‘aesthetic’ consciousness arising from art is an ability to understand what is good or bad as it were, what is right and what is wrong. These judgements run across the social, the political, the cultural and the environmental on a global scale. A moral proposition is predicated on knowledge of the object at hand, that we do not merely experience a moral sensibility, but derived moral knowledge as an outcome. The moral responsibility when assigned to a creator, is one that demands the creator has knowledge of how and with what, he/she creates their art.

The key challenges all artists interested in employing AI in practice will face are in the ontology of practice and being. To fully understand how technology works, how generative AI for example is manipulated and implemented; and ultimately, how AI will influence the substance of humanity in art. It is up to the artist to innovate interventions that maintain the transparency between human intelligence and AI, such that we continue to foster criticality in the space of human existence and human evolution.

Cover Image: Students acting as presenters in a Douyin ‘live’ stream with studio photos of the costumes worn by television actors for บุพเพสันนิวาส or‘Love Destiny’, a famous television serial set in the Kingdom of Ayutthaya © NAFA

Read the first article of the series by Dr Bridget Tracy Tan on what creating art in the digital era entails here.

References

2. https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2017/05/article_0003.html

3. This is a deliberate parody on ‘biological mimicry’.

5. There are numerous studies and evaluations. Two examples are referenced here for information. https://hbr.org/2021/03/ai-should-augment-human-intelligence-not-replace-it & https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2022/09/29/ai-versus-the-human-brain/?sh=44e7e9cb6712

6. บุพเพสันนิวาส or ‘Love Destiny’ is an incredibly popular amongst Thai youths and older generations alike. The storyline involves a modern day protagonist who is knocked out and wakes up to a different era in history, specifically that of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya in Siam.

7. Still image, performance by NAFA Theatre (Mandarin drama) students © NAFA

8. AI and algorithms are deployed in both platforms

9. Still image, performance by NAFA Theatre (Mandarin drama) students © NAFA

10. https://stablediffusionlitigation.com/pdf/00201/1-1-stable-diffusion-complaint.pdf

12. Ibid.

About the Author

Dr Bridget Tracy Tan is Director for the Institute of Southeast Asian Arts and Art Galleries at Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. Formerly a curator at the Singapore Art Museum (now National Gallery Singapore), she holds a First Class Honours degree in History of Art. Her PhD in practice-led research as a curator and critical art historian was obtained from the University of the Arts London. The thesis critically explored Southeast Asian museology and Southeast Asian curating in contemporary paradigms that extend into global platforms, specifically biennales. Dr Tan continues to assemble exhibitions and facilitate the teaching of Southeast Asian arts. She has contributed essays and articles on local and regional artists in seminal publications. Over the last two decades, she has also judged regional and international competitions for photography and painting.

Similar content

deadline

12 Nov 2019

from - to

25 Oct 2018 - 27 Oct 2018

deadline

30 Apr 2019

deadline

30 Nov 2021