Towards a Gender Equity in the Arts

This article is the result of the research conducted by Klaudia Chzhu during the e-residency Virtual Crossovers, organised in April 2021 by ASEF and ENCACT, the European network for cultural management and policy. Klaudia worked closely with her mentor Kiwon Hong to research gender equity in arts, with a particular focus on policies and gaps for visual artists in Europe.

Introduction

Reaching gender equality and empowering all women is proclaimed as the 5th Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) by the United Nations, from which the artistic sphere should not be exempt. Gender disparity in the arts is a pressing problem in the 21st century. There are many issues that must be addressed by arts institutions and managers to ensure a comfortable and level-playing field for artists.

A new UNESCO report published in 2021 on Gender and Creativity: Progress on the precipice highlights the power of robust data-gathering and indicates the areas it should focus on in the future. It also provides a wide variety of transformative gender policies and measures: from increasing the visibility of women and gender diverse artists, to mentoring and training schemes, opening up funding and ensuring it is accessible in the long term. (See Report pg. 54)

This article will focus on some of the issues that artists have been facing according to their gender and will share ideas for solving them. It is based on researched material covering gender equity issues in the arts and on several interviews with artists from different countries conducted in April 2021. The geographical scope of the article is limited to Europe and the focus is on visual arts as an art form.

Interviewing Artists on Gender Parity

In the framework of my one-month participation in the Virtual Crossovers e-residency for emerging arts journalists, I interviewed 26 artists from different European countries. This interview, albeit with a small number of respondents, helped me to look at gender issues from an artist's point of view. The artists were asked the following questions:

- Do you feel gender inequality being an artist?

- What problems do you face (or your fellow artists)?

- Do you have difficulties combining work life and personal life (e.g. taking care of baby/yes)?

- If yes, explain the obstacles you face. Could you mention examples of good practices you were involved in or you know that contribute to gender equity?

- What problems does this practice solve?

The interviews conducted with the artists have identified 3 different groups of answers: the first group of respondents indicated that they have no gender barriers as artist, mainly because of their male identity; the second group acknowledged that as female artists, they have to work twice as much; and the third group did not pay any special attention to gender issues in the arts.

However, the existence of gender inequality can even be traced in the very words of respondents, as quoted in some of the responses below:

‘I’m a man, so I believe there is really a huge inequality towards women…’; ‘As a male artist I have not had episodes of gender inequality…’.

It is a pity that no one answered something like ‘I do not have any gender-based challenges being an artist, maybe because I am a woman!’ It is an ideal reply, and yet still unimaginable, isn't it? This shows that there is a gap in the balance between the genders working in the same area. Nevertheless, we know where to head towards -- the answer that was illustrated above.

There is no doubt that many gender-based gaps still need to be tackled. Two major aspects that will be described in this article are the difficulties in reconciling work and personal life, and the lack of representation of women artists in arts institutions.

Reconciliation of Work and Family Life

Artistic and cultural work, like any other kind of work, is subject to equal opportunity policies, employment rights, and various means of protection like all other workplaces, as enshrined in the 1980 Recommendation concerning the Status of the Artist as well as in the UNESCO 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. Both should serve as inspiration for people and countries to embark on this path towards gender equity.

However, it is difficult for artists to combine work with raising children due to the nature of the artistic work. Given the fact that artists usually work from home or in their studios, the process of setting up, assembling, disassembling, or any other type of art product that may be created, often takes a long time. In this context, parenting can be difficult especially for single-parent families, not only for single mothers but also fathers. In order to create a comfortable environment for artists, it should be common practice for institutions to cover childcare costs. Other obstacles are also linked to the need to travel with children and the specific school requirements that need to be taken into account.

Below are some of the answers from the interviewed artists about issues related to work-life balance:

‘Yes, years ago I worked three part-time jobs and had two children in school. It was tough as a single mother’.

‘I am a single mom, it’s full-time parental duties. A full workday as a professional artist sometimes costs more in childcare than I can make from a sale’.

These answers confirm that there is a real obstacle for artists who are also parents.

The paper entitled How Not To Exclude Artist Parents: Some Guidelines for Institutions and Residencies written in 2021 by Hettie Judah and a group of artist mothers, offers a set of recommendations on how entities and managers can contribute to reduce obstacles related to parenting during artistic production. The paper proposes actions such as carefully paying attention to gaps in the artist’s CV that may be linked to maternity/paternity leave, or to make it a standard practice of understanding the artist’s family circumstances at the outset of a project.

Unequal Representation and Gender Mentioning

Another big gender gap is associated with unequal representation in the arts, whereby female artists are under-represented at museums, galleries, and auctions.

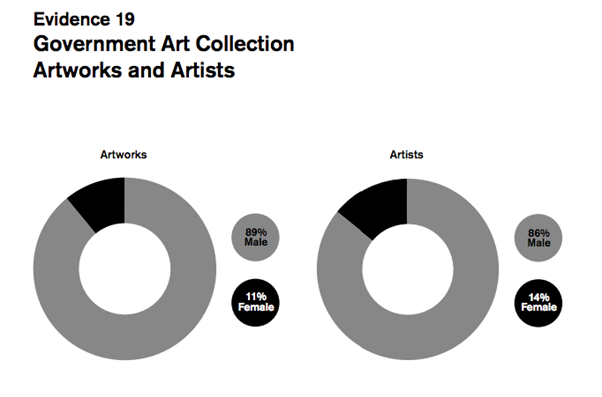

The Representation of Female Artists in Britain During 2019 report provides evidence on the representation of female artists in the UK. The pie chart below showcases that out of 14,411 works acquired by the Government Art Collection houses, 10.7% are by female artists where 14.3% represent female artists.

The New York Times reported in 2019 that only 11% of art acquired by the top museums worldwide for their permanent collections was by women and 14% of all exhibitions were either solo shows featuring female artists or group exhibitions in which the majority of artists were female.

In addition, the female artists who were interviewed also responded that they face a lack of attention on the part of festivals or exhibitions organizers and that they need to prove their talent much more.

Future perspectives

It is clear that we need empathy and solidarity, we need to hear from each other and support each other. In an ideal world, we would not have answered something like ‘As a man, this is quite a hard one for me to answer about gender inequality. I can't really speak for anyone else so let others give their experiences here…’, we would have rather tried to answer from a female perspective and try to understand the problems other artists are facing.

Solving gender inequality requires not only the action and participation of female artists, but the involvement of all artists. If all the artists understand and acknowledge the existence of gender inequality, a sense of openness and proactive approach can help to raise awareness on the issue. It is also clear that not only institutions must introduce innovative measures to reach equality, but artists of all identities need to stand for their rights too. The ability to empathize is the key to feeling and understanding the problem, and ultimately finding common solutions. The mutual written or unwritten arrangements between genders would lead to balancing, agreeing, as an example, not to mention gender category in papers such as CVs, bios, or artists’ statements, in order for artists to be assessed only for the quality of their work. Another aspect could be an agreement that provides childcare costs coverage as a basic need for artists who are parents.

Interviews showed that some artists are not aware of obstacles their fellow artists have. The role of institutions and individuals is instrumental in that sense: they should encourage group discussions, talks, and other kinds of conversational formats with participatory approaches for artists that can facilitate dialogues and solutions to the problems.

Credits cover image: A detail of the work entitled ‘Creation’ by Erin Haldrup Perrazzelli. From Pinterest

Klaudia CHZHU is an emerging arts and cultural manager from Russia. She studied History at the Moscow State University, specializing in Modern and Contemporary History of Europe and America, majoring in Sino-American relations during WWII. She holds MA in Arts & Cultural Management from Universidad Internacional de Cataluña (UIC Barcelona). Together with her master’s colleague from Iran, Klaudia defended the masters’ final project on Saving Cultural Heritage in times of conflict. After completing her study, she founded Art & Culture Inside, an online platform covering Contemporary Art and Cultural Heritage. Throughout 2021, Klaudia has been selected as one of the European Heritage Youth Ambassadors representing Russia and its cultural heritage by reporting for European Heritage Tribune, networking with other Youth Ambassadors and taking part in ESACH and Europa Nostra activities.

Similar content

By Kerrine Goh

30 Jun 2004

posted on

03 Oct 2018

posted on

22 Sep 2022

from - to

08 Mar 2017 - 15 Mar 2017