Wasteland Twinning | Nottingham UK - Yogyakarta Indonesia

[gallery]

[gallery]The Wasteland Twinning Network (WTN) hijacks the concept of ‘City Twinning’ and applies it to urban wastelands in order to generate a transdisciplinary network for parallel research and action. By subverting the City Twinning concept that aims to parade a city’s more predictable cultural assets and shifting the focus to wastelands, new questions of value and function are raised. WTN highlights urban wastelands as spaces continually recreated by a complex web of natural, economic and social relations.

Since its inauguration in 2010 the network has grown to profile urban wasteland sites in 14 cities with project partners in Europe, Asia, USA and Australia. The Wasteland Twinning Network Forum 2012 at the ZK/U (Center for Art and Urbanism, Berlin) brought together international project partners from the network alongside invited practitioners working across disciplines from curatorial practice and urban geography to activism and art. This article is based on a presentation that took place at the Forum, responding to the recently signed 'Wasteland Twinning Agreement' between the wastelands known as Ledok Timoho in Yogyakarta and The Island in Nottingham. The conversation reflects on experiences of researching these sites and examines wider questions about cultural perceptions of wastelands.

Wastelands are often defined by what is missing. However, these urban sites are rarely ‘empty’, but are saturated with layers of history and meaning. Through looking at the existence of and attitudes towards wastelands in different cultures, we begin to consider how ideas of 'empty space’ and various forms of ‘haunting’ perceptions of urban wastelands – and the questions we need to consider as artists and researchers working in these sites.

How is 'wasteland' defined and perceived in Indonesia and the UK?

Ferdiansyah Thajib: In the Indonesian language, the term 'tanah kosong’ - meaning vacant lot, empty land, or empty soil - is often used. Wastelands are usually fenced and inaccessible to the public, but as you move to city outskirts there are fewer fences and they are used as small-scale farms, sports grounds or for small businesses such as food stalls or plant markets.

The status of wastelands is complicated further in Yogyakarta as the region was given special administrative status to honour its service during Indonesia’s struggle for independence, and is the only province in Indonesia that is still governed by a colonial monarchy - the Sultan of Yogyakarta. This has lead to two forms of land ownership law in Yogyakarta - one colonial and another from the modern state, which has lead to four proprietary forms: the Sultan’s Grounds and Pakualaman (the prince's) Grounds from the colonial system; and privately owned and State owned land from the modern system. On the surface, the Sultan owns the majority of the land in Yogyakarta but in reality much of this is used by private and public initiatives who negotiate different use rights (ranging from building to cultivating). Much wasteland in Yogyakarta is thus subject to ambiguous land property regulation, overlapping ownership and competing temporal notions over land values and function.

Rebecca Beinart: In the UK, wasteland sites are temporarily empty plots in cities where an old building has been demolished and a new development is awaited. They are often referred to as ‘brownfield’ sites, meaning they were previously occupied by industry or housing. Categorising land as a brownfield site means it is easier (legally) to rebuild on these plots, compared to ‘green belt’ agricultural land. Most of these sites are owned privately, but they are subject to UK planning legislation and local government policy.

Urban wastelands are often fenced off, but people find ways to access them and they are used in a variety of ways - as temporary recreation grounds, hide-aways, or sites for ‘urban exploration’. Sometimes they are relatively ‘untouched’ for long periods and host diverse plant life, becoming small urban wildernesses.

Tell me about the wasteland site you are researching.

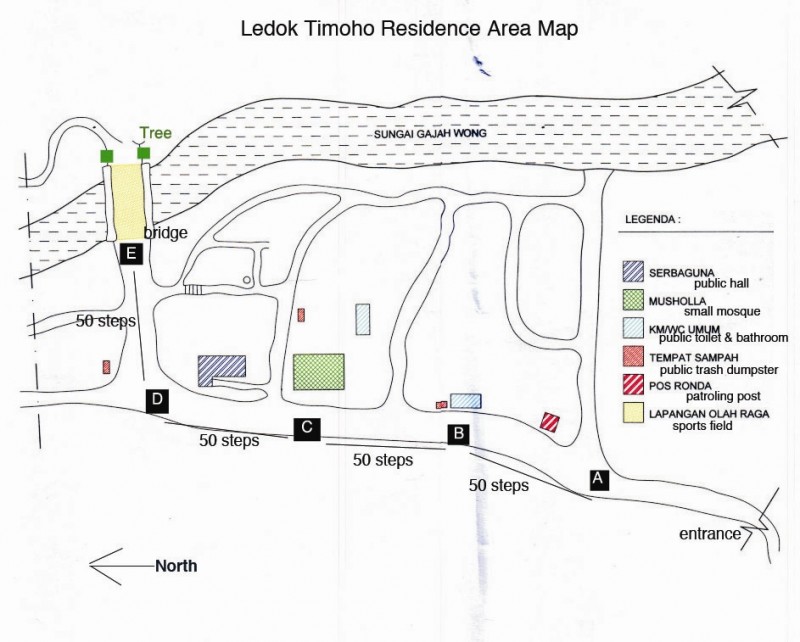

FT: Ledok Timoho is situated on the banks of the Gajah Wong River, near the eastern border of the city of Yogyakarta. The area filling the western promontory of the river is occupied by some 30 semi-permanent houses, with 50 families of street people living there since around 2000. The location is surrounded by housing projects and the entrance is a gateway tucked in between the row of houses. On the eastern side lies the Gajah Wong river and an abandoned bridge - unusable since the city plan to install the connecting road has been frozen for nearly 15 years. Some say that the Ledok Timoho community was started by the bridge as - soon after the construction was finished in 1998 - two families started using cabins which were left by the workers.

In 2009 the inhabitants of Ledok Timoho conducted a self-funded refurbishment programme and developed basic public facilities including a mosque and a communal toilet. The local authorities refuse to give formal recognition to the inhabitants and the status of the land is disputed: in the eyes of the state, it is empty of people. As a result, people living there cannot access health and social welfare assistance from the government.

RB: The Island in Nottingham is a post-industrial site situated between the inner-city area of Sneinton and Nottingham city centre. It has been derelict for twenty years since the Boots pharmaceutical factories that occupied it for most of the twentieth century were demolished. The Island acquired its name in the nineteenth century when canals surrounded the site on three sides. The canals and the railway developed at that time provided key transport links and made the Island a desirable industrial site. In the 1980s, the canals were filled in and Boots moved away, leaving a gap in the city that seemed to hold much promise for the fast developing financial and business sectors in the UK. However, despite various redevelopment plans which have included a Tesco superstore, a ‘vibrant mixed use urban quarter’ and a luxury marina, the site remains undeveloped.

A single road traverses it and divides the publicly accessible part of the site on the north from the fenced off area on the south. The northern part of the wasteland is used by dog-walkers and those seeking a short cut to the city centre or railway station. The fenced section of land contains the burnt out shells of two former railway warehouses. These are listed buildings, and remain as precarious industrial ruins.

How is the site perceived from outside and how does this contrast with the view of people living in or using these sites?

FT: The term empty in ‘tanah kosong’, from a distant observer, is always already related to its economic future as asset or property, despite the fact that people may be present, as they are in Ledok Timoho. The elitist discourse over space treats people occupying the space as ghosts who - in certain situations - need to be exorcised. These approaches are not limited to the state or developers alone, but are widespread practices within capitalism and neoliberalism, positing wastelands both as a resource and an arena where contested rights to the city are played out.

Through the Ledok Timoho experience it’s possible to see how inhabitation provides an alternative model to the elitist discourse of space. In this culture, inhabiting a place takes into account all living and non-living forces existing within its perimeter. Every now and then, when new construction is planned amongst Ledok Timoho inhabitants - which often involves clearing plants - they will conduct a ritual to appease the spirits, reminding themselves that in order to occupy a site they need to take into account and work with all its aspects.

In the face of controlling forces of capital and state, the inhabitants also embrace their assigned roles as ghosts who continuously employ different strategies in negotiating their rights to the city space. There are three modes commonly used in local languages in terms of inhabiting space: ngeyel (insisting on staying, even without any apparent reason), mburaq (the act of desperation), and ndelik-an (haunting, hide and seek game).

One of our collaborators created a map based on the inhabitants' stories and site observation. In contrast to the distant birds-eye view, from this frogs-eye perspective the wasteland no longer appears as a ‘blank spot’ but unfolds rich narratives, emotional investments and patterns of social interaction. Here wasteland becomes a living environment and a place of belonging.

RB: Since the demolition of the Boots factories, the Island has been seen as a 'blank canvas' by developers and a number of architectural plans have been projected onto it, so it becomes a sketchpad for the future. From the perspective of local government, the Island appears to sit between two points: preservation and transformation. The factory buildings are protected as a site of Industrial heritage, their shells supported by improbable scaffolding to keep them from collapse. But the rest of the site is earmarked for development, generating visions for a future that could transform the city, creating a new sense of purpose and identity. Neither of these perspectives seems to relate to the people who use the site.

The Island is regularly used by a variety of people, as a place to walk dogs, jog, take drugs and even sleep sometimes. Although it is privately owned, it is used as a piece of common land. There are well worn paths criss-crossing the site - 'desire lines' taken as cut-throughs between destinations. There are parts of the Island where you feel invisible and there’s a sense that because it’s a wasteland, behaviours are permitted here that would be disallowed in other public spaces.

We've talked to locals about their perceptions of the site and it is anything but empty. It seems that the Island acts as a site of memory for the city and chronicles the history of Nottingham and it’s development. Everyone has a story about this piece of land. In the Middle Ages, it would have been meadow land or pasture at the edge of the city and was regularly flooded. In the 19th century, railway lines were built on the southern edge of the site and small independent businesses sprung up in the railway arches. There are stories of Jesse Boot starting his business, the factories where famous painkillers were developed, and since the demolition there are stories of dark happenings in the factories, urban explorers scaling scaffolding, sword-fighters practicing their moves, the Dali Lama camping there with his entourage, and rumours of a reservoir of toothpaste left behind by Boots.

How do the local political dynamics around the wasteland inform the approaches you have designed and conducted as researchers?

FT: When we started to work with the community of Ledok Timoho we saw conflicts arising between older and newer residents. Hierarchical power relations are reproduced within the community, despite it being a space 'outside' of mainstream culture. The residents found these conflicts problematic as they need to perform as a 'solid community' in the eyes of authorities in order to gain rights and resources.

Introduced by the community leader as a 'Tim Dokumentasi' (the Documentation team) we managed to gain access to interview and collect archival material. We are not the first group to research Ledok Tomoho, but many previous research results did not circulate back into the community, as they were published in limited circles such as academic journals. Whilst the frequent exposure to research activities have contributed to the community’s resistance to accepting yet another research initiative, the open-ended nature of our artistic exploration granted us opportunities to develop more participatory forms of engagement. We are opening a space to share and learn together (not only between community members but also with us, outsiders) about ways to inhabit a space and how we relate to the wasteland as a living space.

This approach enables us to see alternatives - often overshadowed by everyday politics and necessities of survival - in viewing what constitutes the place we called home while at the same time helping to unravel subtle power relations. We aim to accumulate existing knowledge about how communities inhabit wastelands, and also reintroduce models that allow for reflection on and the practice of different power relations. In the long run, as urban development projects continue to be distant from those most affected by them, what is at stake is not only understanding how we can maintain access to certain spaces but also what we can do if we lose that access and have to begin a whole new set of place-making relations elsewhere.

RB: In Nottingham, we have taken a playful approach to researching the Island, attempting to amplify some of the informal ways in which the site is already used. There's a diversity of people who have an interest in the site, and we are interested in collecting information and ideas from many different perspectives. We've conducted interviews with people with stories to tell about the Island. We've collected archival material that documents the history of the site and unrealised architectural plans for the future. One of our main strategies is to initiate public events on the site, to generate conversation and alternative ways to imagine the Island. We staged a tour with a local historian, and the Wasteland Twinning Rounders Club, inviting people to consider the site as a recreation ground. The Twinning Ceremony between the Island and Ledok Timoho allowed us to project narratives from one site onto the other, and compare the way that 'empty plots' are used and occupied in the UK and Indonesia.

One of the main issues we are concerned with in terms of our role as artists and researchers is the danger of this project being co-opted as part of a regeneration agenda. There is a big question around the ethics of regeneration in the UK – which in some instances involves a previously industrial or working class area being turned into expensive real estate, bars and galleries, so that the original population can no longer afford to live or work there. Artists and squatters can be unwittingly complicit in this process – entering derelict buildings and turning them into desirable destinations. There is a wider question here about the ways in which counter-cultural movements are subsumed by capital. But we are interested in looking at groups who manage to work with sites and communities in a way that amplifies what's there already and – whether preservation or transformation is on the agenda – puts these people at the centre of imagining this process. It's interesting for us to see how KUNCI approach working with Ledok Timoho, and to be part of a critical dialogue around these issues within the Wasteland Twinning Network.

The Wasteland Twinning Network Forum was supported by Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF) and Arts Network Asia (ANA) as part of the programme Creative Encounters: Cultural Partnerships between Asia and Europe, the European Cultural Foundation and Arts Council England.

Ferdiansyah Thajib is a co-director of KUNCI Cultural Studies Centre, in Yogyakarta. He finished his studies at the Graduate Program of Religious and Cultural Studies, Sanata Dharma University Yogyakarta, in 2006. Thajib has been actively working as a researcher in the field of cultural studies both as an individual and collaborative contributor. His interests include media and technology, performance studies, critical sexuality studies, and anthropology of emotion as well as space and culture. He is currently a PhD candidate at the Institut für Ethnologie at the Freie Universität in Berlin.

Rebecca Beinart is a member of the Wasteland Twinning Nottingham Collective. She graduated from an MA in Arts and Ecology at Dartington School of Art in 2008. She works as a freelance artist and educator. Her projects explore the territory between art, ecology and politics and take the form of live events in public places, installations and interventions.

The Island Nottingham

http://wasteland-twinning.net/sites/nottingham-england/

Ledok Timho Yogyakarta

http://wasteland-twinning.net/sites/yogyakarta-indonesia/

Wasteland Twinning Network is co-directed by Will Foster, Alex Head, Lars Hayer and Matthias Einhoff

http://wasteland-twinning.net/

Similar content

posted on

18 Aug 2014

from - to

14 Apr 2016 - 14 May 2016

from - to

07 Jun 2016 - 28 Jun 2016