Greater Mekong Symposium Discusses Protection of Cultural Property

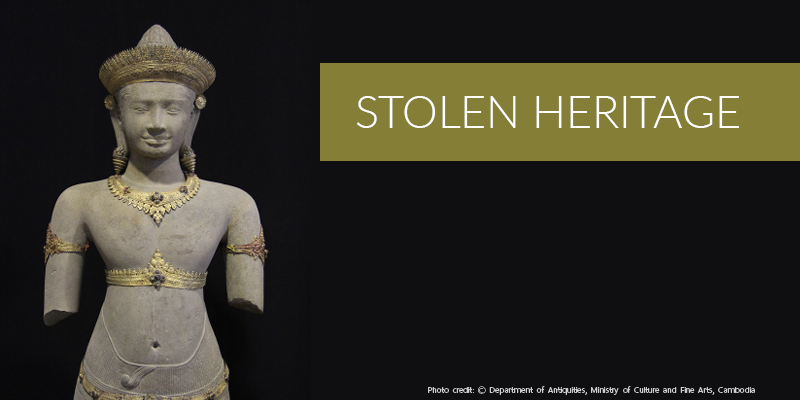

The jewelry once adorned a statue of the god Vishnu, a representation of the prestige and power of the kings of the ancient Khmer Empire. About 50 years ago, in the then-prevailing climate of instability in South-East Asia, the golden crown, necklace, earrings, armbands and breast ornaments were looted from Cambodia, beginning a decades-long journey of transactions spanning Asia, North America and Europe. And then, in recent years, they were rediscovered – in the catalogue of an art dealer based in London.

The trade in antiques and historical art too often lends a veneer of respectability to the theft of such cultural objects, robbing people of their heritage and an understanding of their past. “Even recently in 2017, around 80-90% of Cambodian people didn’t know about the set of gold jewelry that they used for the god during the Angkor period,” said Heng Kamsan, Director of the Department of Antiquities, Cambodia’s Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, who helped to lead the effort for the antiques to be repatriated to Cambodia.

“It was really difficult to collect the documentation for the provenance to negotiate with the current owner [in London] … We have some examples that remain on the bas reliefs in Angkor Wat and Bayon Temple. We used all of this for the provenance too.”

Law enforcement – not to mention conservation and curation – at point of origin is essential to prevent cultural objects from being stolen and removed from the context that lends them so much significance, but trafficking is innately a transnational challenge. In most cases, South-East Asian cultural objects are being transported via neighbouring countries before being shipped abroad.

International coordination is crucial to interrupt trafficking networks, but it has been lacking. In recent efforts in mid-June to strengthen interdiction and repatriation efforts, UNESCO and the Thai National Commission for UNESCO co-organized the Greater Mekong Sub-regional Symposium on International Cooperation to Protect Cultural Properties in Bangkok, hosting law-enforcement officials and government representatives from Cambodia, China, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Viet Nam, as well as other delegates and international experts.

“International borders still provide the best opportunity to intercept stolen cultural objects,” said Kazushige Saito, an intelligence analyst with the Regional Intelligence Liaison Offices for Asia and the Pacific, World Customs Organization. “Unfortunately, customs officers in this region are not equipped with well-rounded knowledge to understand cultural object’s value and identify them in a mass of transported items.”

The task is complicated because combatting the trafficking is necessarily interdisciplinary, requiring the cooperation of not just Customs, law enforcement and policy-makers, but also experts in antiquities and cultural heritage. Identifying contraband cultural objects and differentiating them from licitly traded replicas can be extremely technical, while the proper handling of actual historical treasures is essential to prevent further harm.

The June symposium followed on an operations-level workshop on “Countering Trafficking of Cultural Objects in the Containerised Supply Chain” held in March, co-hosted by UNODC and UNESCO, which also convened personnel from across the region and included specific training in proper handling and storage of seized goods. The Container Control Programme, a partnership between UNODC and World Customs Organization (WCO), illustrates the scale of the challenge, with 720 million containers shipped worldwide each year, only a small fraction of which are thoroughly inspected. Law enforcement and Customs employ systemic approaches regarding distinguishing features of cargo and shipping patterns to target contraband, which requires extensive international coordination.

The regional forums are also opportunities to bring international resources to bear. Existing transnational law-enforcement structures such as Interpol have been working on multiple forms of illegal trafficking for decades, while ASEAN is moving towards more regional law enforcement. There are also international bodies in the legal and cultural spheres, such as International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT), International Council of Museums (ICOM), that support upscale dialogue on cultural heritage protection and conservation, providing additional resources for law enforcement.

“There are various applicable tools for Customs and police to use,” said Etienne Clement, UNESCO expert on Law and Cultural Heritage. “For instance, the Red List database issued by ICOM presents the cultural objects that can be subject to smuggle, helping police to identify the objects and decreasing the risk of being exported. Also, a training handbook by WCO on the prevention of illicit trafficking of cultural heritage, or PITCH, offers insight on techniques and mechanisms of illicit trade.”

The international commitment is enshrined in the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import and Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970). The Convention emphasizes the significance of cultural objects to the survival of communities, and that looting and smuggling can impair human rights and economic opportunities at the grass-roots level. Signed by 140 countries, the Convention calls for countries to prevent the consequent harm to people’s livelihoods, identity and dignity, at both the national and global level.

Mechanisms include a series of measures such as inventories of cultural objects, export certificate systems, monitoring of trade, imposition of penal or administrative sanctions, and the educational campaigns. The Convention also has a number of provisions on the restitution of objects and international cooperation.

Not all countries in South-East Asia are signatories, however, which in some cases results in ad hoc arrangements based on negotiations and bilateral ties. In the situation involving the Khmer jewelry, Heng Kamsan and his colleagues’ efforts over many trips to the United Kingdom resulted in repatriation to Cambodia in 2017. The artwork is exhibited at the beginning of each year at the National Museum of Cambodia, although there are associated security concerns, and has become a centerpiece of raising awareness about history and learning about the country’s legacy.

Aspects of raising awareness, both among the general public and in terms of political will, are also essential to stemming the illicit trade. Foreign tourists need to be educated not to buy cultural objects instead of replicas, while each country’s citizens should be aware of the significance of heritage to their societies and their own lives, as well as the responsibility to protect it. The combined international effort is also an attempt to urge policy-makers in each country to prioritize cultural objects both domestically and for regional cooperation.

“It is a good idea that customs and police work together and with the culture sector,” Hla Han, a Myanmar officer in the Criminal Investigation Department, said. “We need to find out what we are missing and how the criminals are always one step ahead of us in this fight. This multi-agency training is timely as trafficking crimes in South-East Asia have become serious. We, at the operational level, can only hope that leaders will finally see the need to set up a real cooperation mechanism with focal points working in all concerned agencies.”

By sharing ideas and experiences, as well as outstanding challenges, officials from across the region were able to identify key areas to improve coordination, especially at the operational level, such as dedicated law-enforcement teams for cultural objects and identifying focal points in each country to facilitate contact. But there is also a shared urgency – as legitimate commerce becomes more globalized and sophisticated, so too do criminal networks whose activities are often interlinked in stolen objects, arms, drugs and human trafficking. There is a growing commitment to cooperation to fight the illegal trade in cultural objects, but also a shared awareness that the task will continue to grow more difficult in the future.

The jewelry once adorned a statue of the god Vishnu, a representation of the prestige and power of the kings of the ancient Khmer Empire. About 50 years ago, in the then-prevailing climate of instability in South-East Asia, the golden crown, necklace, earrings, armbands and breast ornaments were looted from Cambodia, beginning a decades-long journey of transactions spanning Asia, North America and Europe. And then, in recent years, they were rediscovered – in the catalogue of an art dealer based in London.

The trade in antiques and historical art too often lends a veneer of respectability to the theft of such cultural objects, robbing people of their heritage and an understanding of their past. “Even recently in 2017, around 80-90% of Cambodian people didn’t know about the set of gold jewelry that they used for the god during the Angkor period,” said Heng Kamsan, Director of the Department of Antiquities, Cambodia’s Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, who helped to lead the effort for the antiques to be repatriated to Cambodia.

“It was really difficult to collect the documentation for the provenance to negotiate with the current owner [in London] … We have some examples that remain on the bas reliefs in Angkor Wat and Bayon Temple. We used all of this for the provenance too.”

Law enforcement – not to mention conservation and curation – at point of origin is essential to prevent cultural objects from being stolen and removed from the context that lends them so much significance, but trafficking is innately a transnational challenge. In most cases, South-East Asian cultural objects are being transported via neighbouring countries before being shipped abroad.

International coordination is crucial to interrupt trafficking networks, but it has been lacking. In recent efforts in mid-June to strengthen interdiction and repatriation efforts, UNESCO and the Thai National Commission for UNESCO co-organized the Greater Mekong Sub-regional Symposium on International Cooperation to Protect Cultural Properties in Bangkok, hosting law-enforcement officials and government representatives from Cambodia, China, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Viet Nam, as well as other delegates and international experts.

“International borders still provide the best opportunity to intercept stolen cultural objects,” said Kazushige Saito, an intelligence analyst with the Regional Intelligence Liaison Offices for Asia and the Pacific, World Customs Organization. “Unfortunately, customs officers in this region are not equipped with well-rounded knowledge to understand cultural object’s value and identify them in a mass of transported items.”

The task is complicated because combatting the trafficking is necessarily interdisciplinary, requiring the cooperation of not just Customs, law enforcement and policy-makers, but also experts in antiquities and cultural heritage. Identifying contraband cultural objects and differentiating them from licitly traded replicas can be extremely technical, while the proper handling of actual historical treasures is essential to prevent further harm.

The June symposium followed on an operations-level workshop on “Countering Trafficking of Cultural Objects in the Containerised Supply Chain” held in March, co-hosted by UNODC and UNESCO, which also convened personnel from across the region and included specific training in proper handling and storage of seized goods. The Container Control Programme, a partnership between UNODC and World Customs Organization (WCO), illustrates the scale of the challenge, with 720 million containers shipped worldwide each year, only a small fraction of which are thoroughly inspected. Law enforcement and Customs employ systemic approaches regarding distinguishing features of cargo and shipping patterns to target contraband, which requires extensive international coordination.

The regional forums are also opportunities to bring international resources to bear. Existing transnational law-enforcement structures such as Interpol have been working on multiple forms of illegal trafficking for decades, while ASEAN is moving towards more regional law enforcement. There are also international bodies in the legal and cultural spheres, such as International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT), International Council of Museums (ICOM), that support upscale dialogue on cultural heritage protection and conservation, providing additional resources for law enforcement.

“There are various applicable tools for Customs and police to use,” said Etienne Clement, UNESCO expert on Law and Cultural Heritage. “For instance, the Red List database issued by ICOM presents the cultural objects that can be subject to smuggle, helping police to identify the objects and decreasing the risk of being exported. Also, a training handbook by WCO on the prevention of illicit trafficking of cultural heritage, or PITCH, offers insight on techniques and mechanisms of illicit trade.”

The international commitment is enshrined in the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import and Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970). The Convention emphasizes the significance of cultural objects to the survival of communities, and that looting and smuggling can impair human rights and economic opportunities at the grass-roots level. Signed by 140 countries, the Convention calls for countries to prevent the consequent harm to people’s livelihoods, identity and dignity, at both the national and global level.

Mechanisms include a series of measures such as inventories of cultural objects, export certificate systems, monitoring of trade, imposition of penal or administrative sanctions, and the educational campaigns. The Convention also has a number of provisions on the restitution of objects and international cooperation.

Not all countries in South-East Asia are signatories, however, which in some cases results in ad hoc arrangements based on negotiations and bilateral ties. In the situation involving the Khmer jewelry, Heng Kamsan and his colleagues’ efforts over many trips to the United Kingdom resulted in repatriation to Cambodia in 2017. The artwork is exhibited at the beginning of each year at the National Museum of Cambodia, although there are associated security concerns, and has become a centerpiece of raising awareness about history and learning about the country’s legacy.

Aspects of raising awareness, both among the general public and in terms of political will, are also essential to stemming the illicit trade. Foreign tourists need to be educated not to buy cultural objects instead of replicas, while each country’s citizens should be aware of the significance of heritage to their societies and their own lives, as well as the responsibility to protect it. The combined international effort is also an attempt to urge policy-makers in each country to prioritize cultural objects both domestically and for regional cooperation.

“It is a good idea that customs and police work together and with the culture sector,” Hla Han, a Myanmar officer in the Criminal Investigation Department, said. “We need to find out what we are missing and how the criminals are always one step ahead of us in this fight. This multi-agency training is timely as trafficking crimes in South-East Asia have become serious. We, at the operational level, can only hope that leaders will finally see the need to set up a real cooperation mechanism with focal points working in all concerned agencies.”

By sharing ideas and experiences, as well as outstanding challenges, officials from across the region were able to identify key areas to improve coordination, especially at the operational level, such as dedicated law-enforcement teams for cultural objects and identifying focal points in each country to facilitate contact. But there is also a shared urgency – as legitimate commerce becomes more globalized and sophisticated, so too do criminal networks whose activities are often interlinked in stolen objects, arms, drugs and human trafficking. There is a growing commitment to cooperation to fight the illegal trade in cultural objects, but also a shared awareness that the task will continue to grow more difficult in the future.

This article is taken from the website of the UNESCO Regional Bureau in Bangkok. For additional information, please visit https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/joint-effort-mekong-combat-trafficking-cultural-objects

Similar content

posted on

28 Apr 2022